How to Khöömii/ei

Amongst Khöömiich in Mongolia there is not a complete agreement with the name of a style and the techniques used in Khöömii. However Khöömii can be sounded either with a melody of overtones, by using words, or a combination of both. In Tuva there is an agreement with three main styles. It is important to understand that throat singing is not all about overtones and undertones. It is the whole sound including the quality of the drone as well as the intention imbued within the sounds of each individual performer that should be considered. In all styles breathe control and muscle support using the abdomen, small of the back, and an open raised chest are vital. It takes dedicated training master khöömii/ei.

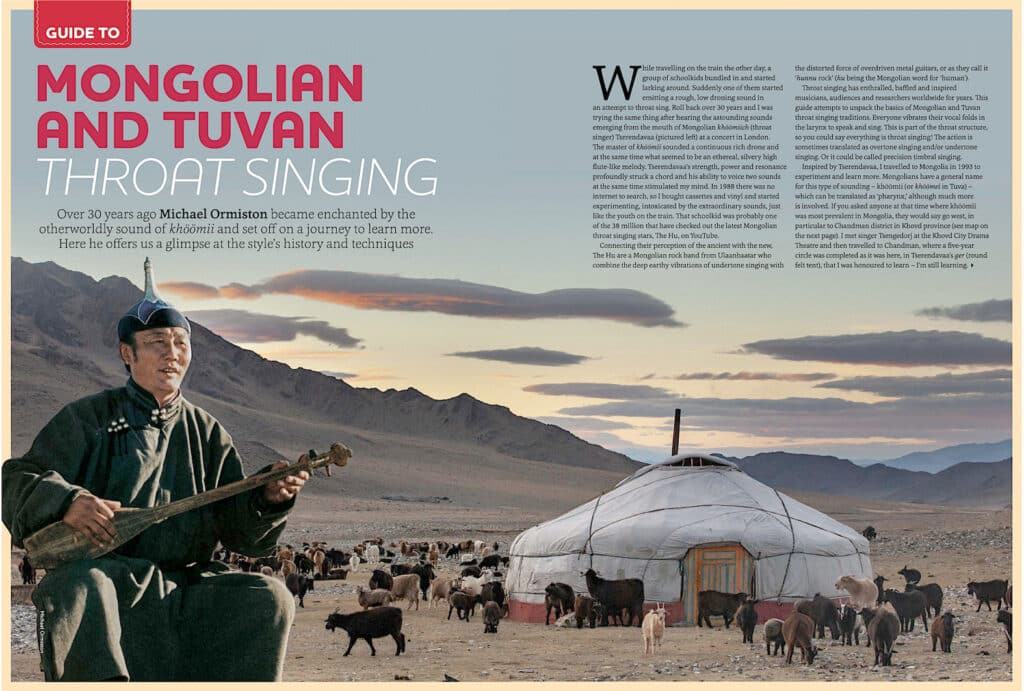

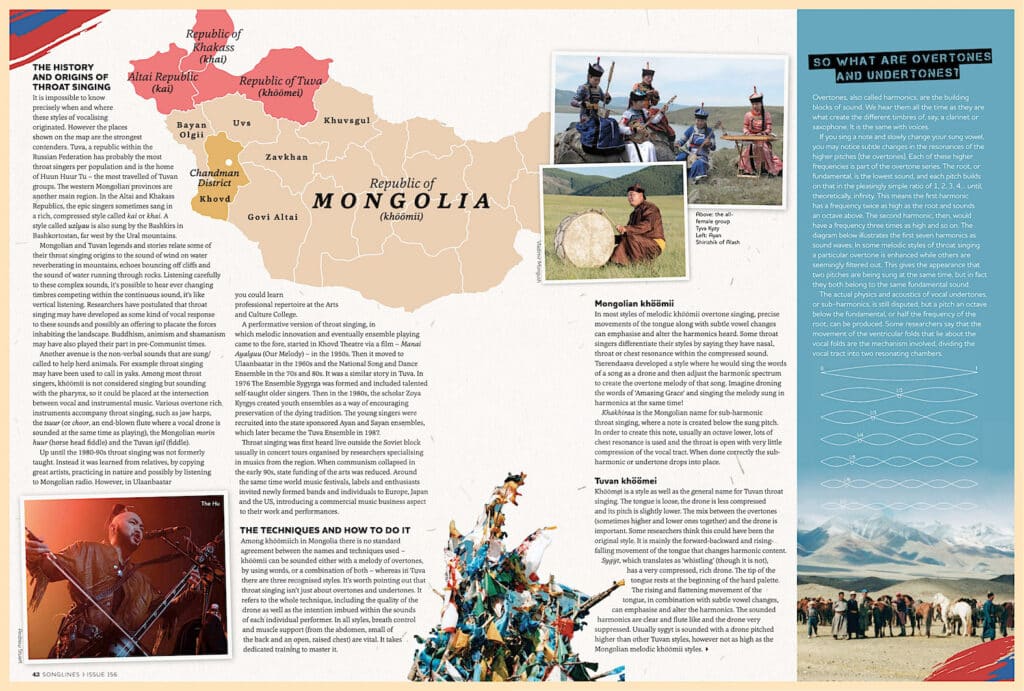

Mongolian Khöömii.

In most styles of melodic Khöömii overtone singing, precise movements of a loose tongue or a fixed tip of the tongue placed at the front of the hard palette in combination with a compressed rich drone along with subtle vowel changes can emphasise and alter the harmonics heard. Some Khöömiich differentiate their styles by saying the have nasal, throat or chest resonance within the compressed sound. Tserendaava developed a style where he would sing the words of a song as a compressed drone and then adjust the harmonic spectrum to create the overtone melody of that song. Imagine droning the words of amazing grace and singing the melody sung in harmonics at at the same time!

Khakhiraa is the Mongolian name for Sub-harmonic throat singing where a note usually an octave (half the frequency) below the pitch sung is created. Lots of chest resonance is used and the throat is open with very little compression of the vocal tract. When done correctly the sub-harmonic or undertone drops into place. Normally overtone melodies are created from that undertone by changes of specific vowel qualities not specifically using the tongue like in the other Khöömii styles. It’s likely that the movement of the vestibular/ventricular folds which reside above our vocal folds are employed.

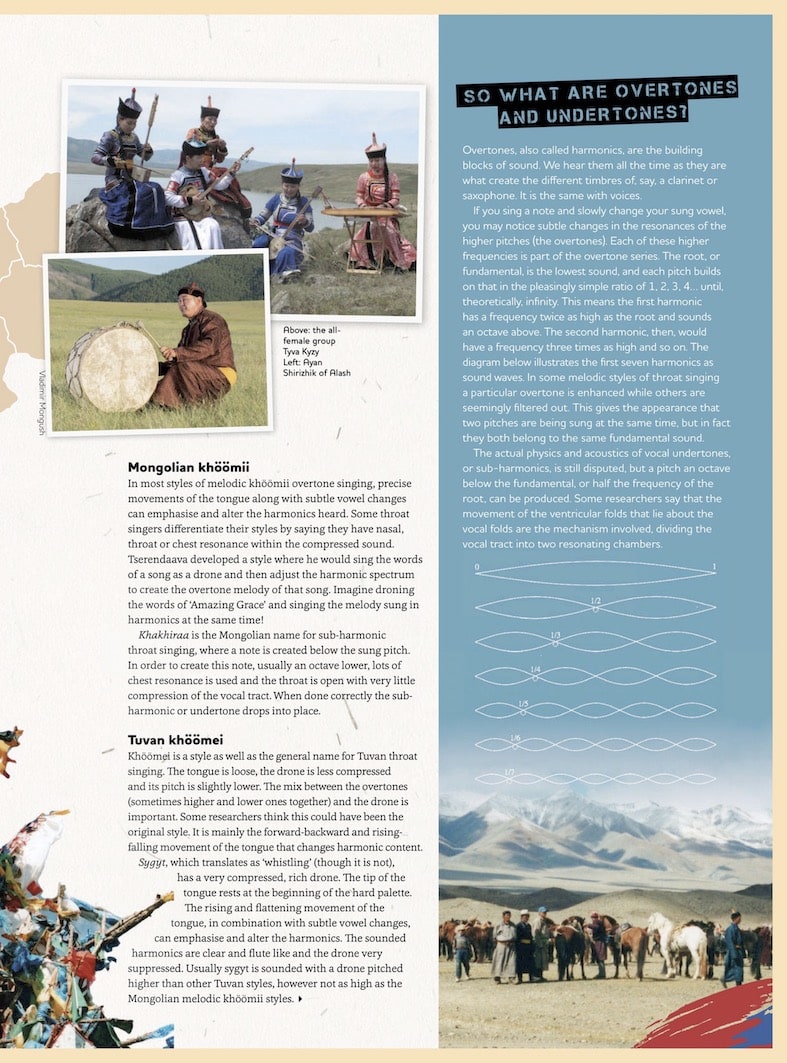

Tuvan Khöömei

Sygyt which means whistling (though it is not) has a very compressed rich sounding drone. The tip of the tongue rests at the beginning of the hard palette. The rising, flattening and movement of the middle, back and root of the tongue in combination with subtle vowel changes can emphasise and alter the harmonics heard. The harmonics are clear and flute like and the drone very suppressed. Usually Sygyt is sounded with a higher drone pitch that the other Tuvan styles. However not as high as the Mongolian melodic Khöömii styles.

Khöömei is the name of a style and the general name for Tuvan Throat singing. The tongue unlike Sygyt is loose and the pitch of the slightly less compressed drone is lower. The overtones heard are not as dominant as with Sygyt. It seems that the mix between the overtones, sometime higher and lower ones together and the drone is important. Some researchers think this could have been original style. Again it is mainly the forward to backward and rising and falling movement of the tongue that changes the harmonic content.

Kargyraa

This is the majestic Tuvan sub-harmonic style and more than likely the Mongolians copied this style. The technique is similar to the Mongolian kharkhiraa, however the Tuvans are masters at creating overtone melodies from their undertones. There are two main types, Mountain Kargyraa and steppe Kargyraa.

Borbangnadyr uses a very rapid movement of the back of the tongue with the same basic sound as Khöömei. This for example can be used to imitate the flow of a small river, sometimes as an offering to the animate spirit-masters of the river. With no specific melody it is up to the singers breathe length, improvisation and inspiration to create each phrase.

Chylandyk is a combination of the undertone of Kargyraa with the high overtone of Sygyt. The late Mongolian Khöömiich Zulsar heard this in the 1990’s to create his own amazing version.

Mongolians and Tuvans have many other sub-styles and innovations are happening all the time. With experimentation it is possible to highlight at least three different overtones whilst singing an undertone. Along with the fundamental making it seem like five sounds are happening at the same time even though it is from one source!

© Michael Ormiston 2020