Scientific American Article September 1999

Theodore C. Levin and Michael E. Edgerton

The Throat Singers of Tuva

Testing the limits of vocal ingenuity, throat-singers can create sounds unlike anything in ordinary speech and song–carrying two musical lines simultaneously, say, or harmonising with a waterfall.

From atop one of the rocky escarpments that crisscross the south Siberian grasslands and taiga forests of Tuva, one’s first impression is of an unalloyed silence as vast as the land itself. Gradually the ear habituates to the absence of human activity. Silence dissolves into a subtle symphony of buzzing, bleating, burbling, cheeping, whistling–our onomatopoeic shorthand for the sounds of insects, beasts, water, birds, wind. The polyphony unfolds slowly, its colours and rhythms by turns damped and reverberant as they wash over the land’s shifting contours.

For the semi-nomadic herders who call Tuva home, the soundscape inspires a form of music that mingles with these ambient murmurings. Ringed by mountains, far from major trade routes and overwhelmingly rural, Tuva is like a musical Olduvai Gorge–a living record of a proto-musical world, where natural and human-made sounds blend.

Among the many ways the pastoralists interact with and represent their aural environment, one stands out for its sheer ingenuity: a remarkable singing technique in which a single vocalist produces two distinct tones simultaneously. One tone is a low, sustained fundamental pitch, similar to the drone of a bagpipe. The second is a series of flutelike harmonics, which resonate high above the drone and may be musically stylized to represent such sounds as the whistle of a bird, the syncopated rhythms of a mountain stream or the lilt of a cantering horse.

In the local languages, the general term for this singing is khöömei or khoomii, from the Mongolian word for “throat.” In English it is commonly referred to as throat-singing. Some contemporary Western musicians also have mastered the practice and call it overtone singing, harmonic singing or harmonic chant. Such music is at once a part of an expressive culture and an artifact of the acoustics of the human voice. Trying to understand both these aspects has been a challenge for Western students of music, and each of us–one a musical ethnographer (Levin), the other a composer with an interest in extended vocal techniques (Edgerton)–has had to traverse the unfamiliar territory of the other.

Voice of a Horse : in Tuvan music, the igil—played here by Andrei Chuldum-ool on the grasslands of southern Siberia (also above)—is a two-stringed upright fiddle made from horse hide, hair and gut and used to re-create equine sounds. Sound mimicry, the cultural basis of Tuvan music, reaches its culmination in throat-singing.

Sound Mimesis.

In Tuva, legends about the origins of throat-singing assert that humankind learned to sing in such a way long ago. The very first throat-singers, it is said, sought to duplicate natural sounds whose timbres, or tonal colors, are rich in harmonics, such as gurgling water and swishing winds. Although the true genesis of throat-singing as practiced today is obscure, Tuvan pastoral music is intimately connected to an ancient tradition of animism, the belief that natural objects and phenomena have souls or are inhabited by spirits.

According to Tuvan animism, the spirituality of mountains and rivers is manifested not only through their physical shape and location but also through the sounds they produce or can be made to produce by human agency. The echo off a cliff, for example, may be imbued with spiritual significance. Animals, too, are said to express spiritual power sonically. Humans can assimilate this power by imitating their sounds.

Among the pastoralists, emulating ambient sounds is as natural as speaking. Throat-singing is not taught formally (as music often is) but rather picked up, like a language. A large percentage of male herders can throat-sing, although not everyone is tuneful. A taboo against female throat-singers, based on a belief that it causes infertility, is gradually receding, and younger women are beginning to practice the technique as well. The popularity of throat-singing among Tuvan herders seems to have arisen from a coincidence of culture and geography: on the one hand, the animistic sensitivity to the subtleties of sound, especially its timbre, and on the other, the ability of reinforced harmonics to project over the broad open landscape of the steppe. In fact, two decades ago concert performances were uncommon because most Tuvans regarded the music as too “down home” to spend money on. But now it leads a parallel public life. Professional ensembles have achieved celebrity status, and the favorite singers are symbols of national cultural identity

The most virtuosic practices of throat-singing are concentrated in Tuva (now officially called Tyva), an autonomous republic within Russia on its border with Mongolia, and in the surrounding Altai region, particularly western Mongolia. But vocally reinforced harmonics can also be heard in disparate parts of central Asia. Among the Bashkirs, a Turkic-speaking people from the Ural Mountains, musicians sing melodies with breathy reinforced harmonics in a style called uzliau. Epic singers in Uzbekistan, Karakalpakstan and Kazakhstan introduce hints of reinforced harmonics in oral poetry, and certain forms of Tibetan Buddhist chant feature a single reinforced harmonic sustained over a fundamental pitch. Beyond Asia, the use of vocal overtones in traditional music is rare but not unknown. It turns up, for example, in the singing of Xhosa women in South Africa and, in an unusual case of musical improvisation, in the 1920s cowboy songs of Texan singer Arthur Miles, who substituted overtone singing for the customary yodelling.

The ways in which singers reinforce harmonics and the acoustical properties of these sounds were little documented until a decade ago, when Tuvan and Mongolian music began to reach a worldwide audience. Explaining the process is best done with the aid of a widely used model of the voice, the source-filter model. The source–the vocal folds–provides the raw sonic energy, which the filter–the vocal tract–shapes into vowels, consonants and musical notes.

HUMAN VOICE is a complex musical instrument: the buzz from the vocal folds (and, in some throat-singing, from the so-called false folds) is shaped by the rest of the vocal tract (left). The buzz is a composite of a fundamental tone (such as low C, with a frequency of 65.4 hertz) and its harmonics, whose frequencies are integral multiples (above). Shown here are the nearest corresponding notes in the equal-tem- pered musical scale; the asterisks indicate harmonics that do not closely align with equal temperament.

Hooked on Harmonics

IAt its most basic, sound is a wave whose propagation changes pressure and related variables–such as the position of molecules in a solid or fluid medium–from moment to moment. In speech and song the wave is set in motion when the vocal folds in the larynx disturb the smoothly flowing airstream out from (or into) the lungs. The folds open and close periodically, causing the air pressure to oscillate at a fundamental frequency, or pitch. Because this vibration is not sinusoidal, it also generates a mixture of pure tones, or harmonics, above the fundamental pitch. Harmonics occur at whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency. The lowest fundamental in operatic repertoire, for example, is a low C note whose conventional frequency is 65.4 hertz; its harmonics are 130.8 hertz, 196.2 hertz (see illustrations above and below) and so on. The strength of the harmonics diminishes as their frequencies rise, such that the loudness falls by 12 decibels (a factor of roughly 16 in sonic energy) with each higher octave (a factor of two in pitch

The second component of the source-filter model, the vocal tract, is basically a tube through which the sound travels. Yet the air within the tract is not a passive medium that simply conveys sound to the outside air. It has its own acoustical properties–in particular, a natural tendency to resonate at certain frequencies. Like the whistling sound made by blowing across the top of a glass, these resonances, known as formants, are set in motion by the buzz from the vocal folds. Their effect is to amplify or dampen sound from the folds at distinctive pitches, transforming the rather boring buzz into a meaningful clutch of tones.

The sculpting of sound does not end once it escapes from the mouth. As the wave wafts outward, it loses energy as it spreads over a larger area and sets the freestanding air in motion. This external filtering, known as the radiation characteristic, dampens lower frequencies to a greater extent than it does higher frequencies. When combined, the source, filter and radiation characteristic produce sound whose harmonics decrease in power at the rate of six decibels (dB) per octave–except for peaks around certain frequencies, the formants [see “The Acoustics of the Singing Voice,” by Johan Sundberg; Scientific American, March 1977; and “The Human Voice,” by Robert T. Sataloff; Scientific American, December 1992].

SOURCE-FILTER MODEL treats the voice as a set of distinct components. The source—the vocal folds—produces a blend of harmonics that are louder at lower frequencies than at higher ones. The filter—the vocal tract—transmits some harmonics (those that line up with its formants) more readily than others. The radiation characteristic of the outside air is a second filter.

In normal speech and song, most of the energy is concentrated at the fundamental frequency, and harmonics are perceived as elements of timbre–the same quality that distinguishes the rich sound of a violin from the purer tones of a flute–rather than as different pitches. In throat-singing, however, a single harmonic gains such strength that it is heard as a distinct, whistlelike pitch. Such harmonics often sound disembodied. Are they resonating in the vocal tract of the singer, in the surrounding physical space or merely in the mind of the listener? Recent research by us and by others has made it clear that the vocally reinforced harmonics are not an artifact of perception but in fact have a physical origin.

FORMING FORMANTS.

Although the vocal folds can produce an amazing variety of sounds, it is the vocal tract that molds the raw sounds into language and music. The tract imposes a pattern on the folds’ composite sound by picking out a certain combination of tones: namely, those that match the natural resonant frequencies of the air within the tract. As people speak or sing, they raise and lower the resonant frequencies—also known as formant frequencies—by moving their tongue, lips and so on. These movements are normally perceived as shifts in vowel articulation.The frequency of the first formant, F1, is inversely related to tongue height (F1 falls as the tongue rises, as during the change from /a/ in“hot”to /i/ in“heed”).The frequency of the second formant, F2, is related to tongue advancement (F2 rises as the tongue moves forward, as when /o/ in “hoe” moves toward /i/ in “heed”).Theoretically, the vocal tract has an infinite number of formants, but the arrangement of the first two or three accounts for most of the difference among vowel sounds. See Below.

To understand why the formant frequencies shift, imagine that the vocal tract is a tube closed at one end (the folds) and open at the other (the lips). Next, imagine that the tube is uniform in cross section, in which case the resonant frequencies are fixed by the length of the tube. For a tube 17.5 centimetres (seven inches) long—roughly equivalent to the vocal tract of an adult male—F1 peaks at 500 hertz, F2 at 1,500 hertz, F3 at 2,500 hertz and so on.

Each resonance represents a standing wave within the tube. In other words, the oscillations of air pressure (which convey the sound) assume a definite pattern; so does the back-and-forth jiggling of molecules that occurs in response to the changing pressure differences along the tube. At certain positions called pressure nodes, the pressure remains constant while the molecules must traverse their greatest distance. At other positions called pressure antinodes, the pressure fluctuates by its maximum amount while the molecules stay put. (One can ignore their random thermal motion, which is not relevant to the choreography of wave motion.) Because the closed end of the tube prevents molecules from moving, it must be a pressure antinode. The end open to the outside air must be a pressure node. Each higher formant adds another pair of node and antinode. See below

Now suppose that the tube is squeezed, as happens when the tongue constricts the tract. The nodes and antinodes still alternate, but the frequency changes in proportion to the amount of squeezing. A constriction near a pressure node lowers the formant frequency, whereas a constriction near a pressure antinode raises it.Enlargement has the opposite effect.These rules of thumb were first explained by Lord Rayleigh a century ago.

At a node, squeezing the tube forces the molecules to pass through a narrower opening. Assuming the pressure difference that propels them remains roughly the same, the air needs more time to complete its motion.The wave must slow down—that is, its frequency must decrease.

At a pressure antinode, the molecules do not move, but their density varies as pressure fluctuations alternately pull surrounding molecules toward the antinode and push them away. Because squeezing reduces the volume of the tube near the antinode, the addition of a given number of molecules produces a larger increase in density, hence pressure. In effect, the system has become stiffer. It responds faster, so the wave frequency increases. A rigorous explanation, based on so-called perturbation theory, considers the new shape the standing wave is forced to assume.

Throat-singers routinely apply these principles. When they press the base of the tongue to the back of the throat, where the second formant has a pressure node, they lower the frequency of that formant. In the Tuvan sygyt style, they push up the middle of the tongue to constrict the antinode of the second formant, thus elevating its frequency. —George Musser, staff writer.

Biofeedback.

The mechanism of this reinforcement is not fully understood. But it seems to involve three interrelated components: tuning a harmonic in the middle of a very narrow and sharply peaked formant; lengthening the closing phase of the opening-and-closing cycle of the vocal folds; and narrowing the range of frequencies over which the formant will affect harmonics. Each of these processes represents a dramatic increase of the coupling between source and filter. Yet despite a widespread misconception, they do not involve any physiology unique to Turco-Mongol peoples; anybody can, given the effort, learn to throat-sing.

To tune a harmonic, the vocalist adjusts the fundamental frequency of the buzzing sound produced by the vocal folds, so as to bring the harmonic into alignment with a formant. This procedure is the sonic equivalent of lifting or lowering a ladder in order to move one of its higher steps to a certain height. Acoustic analysis has verified the precision of the tuning by comparing two different harmonics, the first tuned to the centre of a formant peak and the second detuned slightly. The former is much stronger. Singers achieve this tuning through biofeedback: they raise or lower the fundamental pitch until they hear the desired harmonic resonate at maximum amplitude.

Throat-singers tweak not only the rate at which the vocal folds open and close but also the manner in which they do so. Each cycle begins with the folds in contact and the glottis—the space between the folds—closed. As the lungs expel air, pressure builds to push the folds apart until the glottis opens. Elastic and aerodynamic forces pull them shut again, sending a puff of air into the vocal tract. Electroglottographs, which use transducers placed on the neck to track the cycle, show that throat-singers keep the folds open for a smaller fraction of the cycle and shut for longer. The more abrupt closure naturally puts greater energy into the higher harmonics. Moreover, the longer closing phase helps to maintain the resonance in the vocal tract by, in essence, reducing sound leakage back down the windpipe. Both effects lead to a spectrum that falls off less drastically with frequency, which further

accentuates the desired harmonics.

The third component of harmonic isolation is the assortment of techniques that throat-singers use to increase the amplification and selectivity provided by the vocal tract. By refining the resonant properties normally used to articulate vowels, vocalists reposition, heighten and sharpen the formants. In so doing, they strengthen the harmonics that align with the narrow formant peak, while simultaneously weakening the harmonics that lie outside of this narrow peak. Thus, a single overtone can project above the others. In addition, singers move their jaws forward and protrude, narrow and round their lips. These contortions reduce energy loss and feed the resonances back to the vocal-fold vibration, further enhancing the resonant peak.

SOUND SPECTRA show the difference between normal enunciation of the vowel /a/ in “hot” (left) and throat-singing (right). In both cases the power is concentrated at distinct frequencies—the harmonics produced by the vocal folds (red). When harmon- ics align with the formant frequencies of the vocal tract (black), they gain in strength.

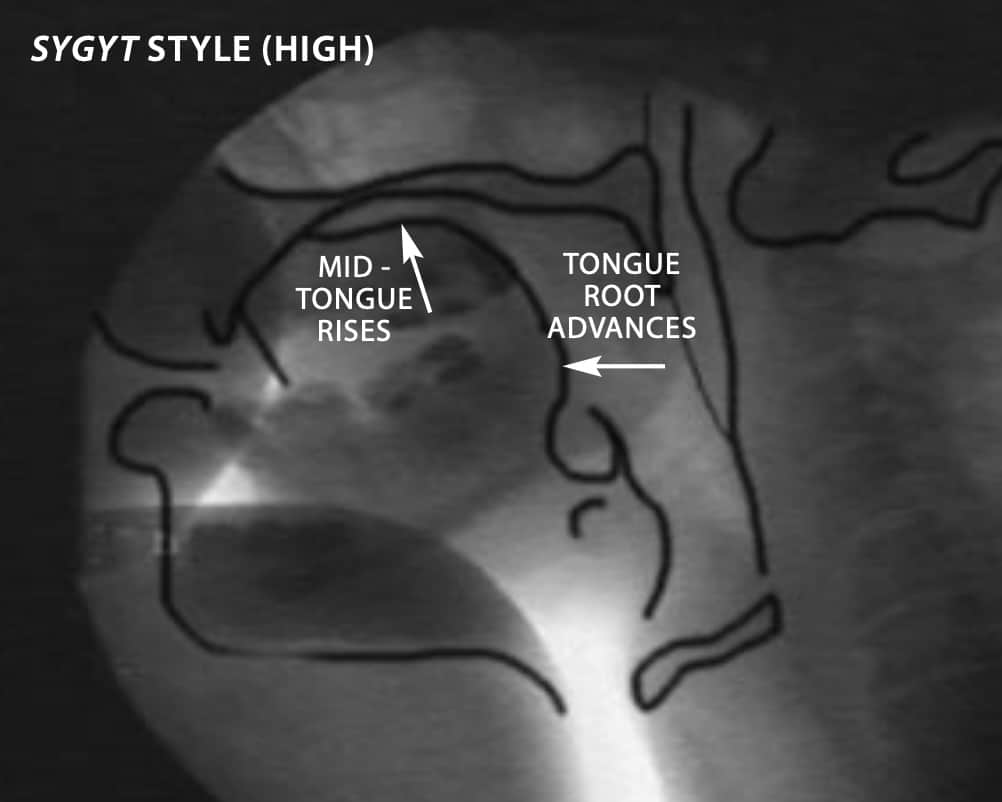

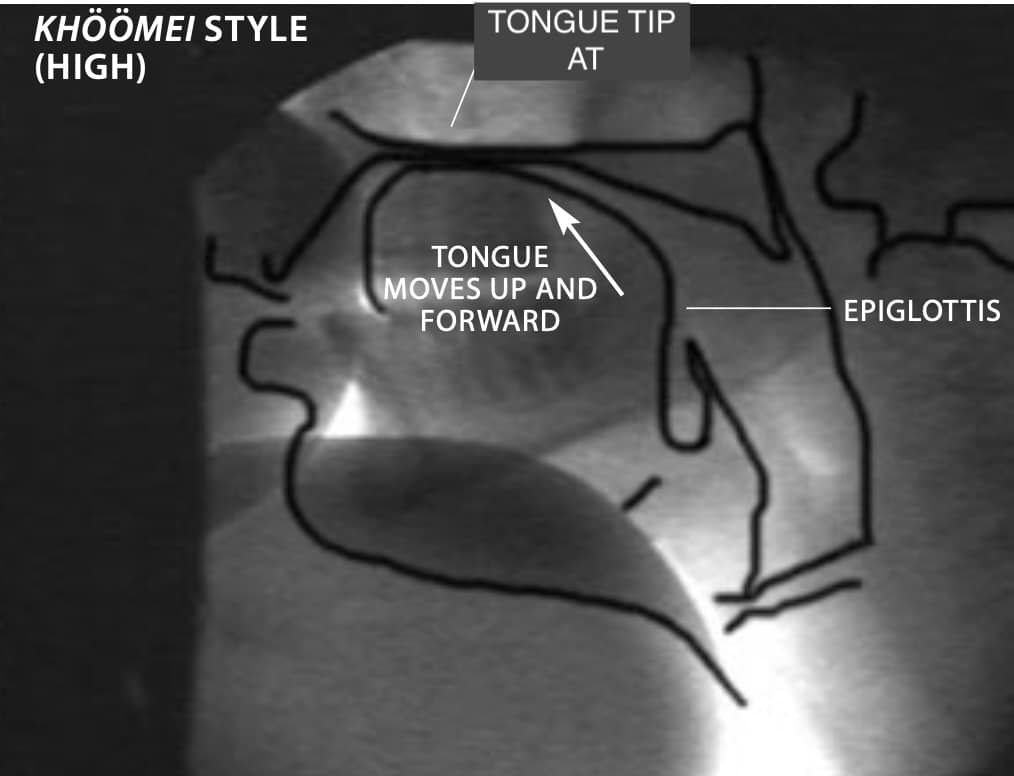

X-RAYS show throat-singers in action. In the Tuvan sygyt style (top row), vocalists keep the tongue tip behind the upper teeth, near the alveolar ridge. To shift from low harmonics (top left) to high harmonics (top right), they bring the middle of the tongue up and he root of the tongue forward. In the khöömei style, the pitch rises as the entire tongue moves from low and back (bottom left) to high and front (bottom right). These motions are obvious in the movies available at www.sciam.com/1999/0999issue/0999levin.html.

In a study of both Tuvan and Western overtone singers conducted at the University of Wisconsin’s hospitals and clinics with support from the National Centre for Voice and Speech, video fluoroscopy (motion x-ray) and nasoendoscopy (imaging the vocal folds using a miniature camera) have confirmed that singers manipulate their vocal tracts to shift the frequency of a formant and align it with a harmonic. By reinforcing different harmonics in succession, they can sing a melody. The nine musicians in the study demonstrated at least four specific ways to accomplish the shifting. Other methods may also be possible.

In the first, the tip of the tongue remains behind the upper teeth while the mid tongue rises to intone successively higher harmonics. Additionally,

vocalists fine-tune the formant by periodically opening their lips slightly. In Tuvan the style of music produced by this means is known as sygyt (“whistle”).

In the second method, singers move the tongue forward, an act that in normal speech changes the vowel sound /o/ (“hoe”) to /i/ (“heed”). The lowest

formant drops, and the second rises. By precisely controlling how much the formants separate, a Tuvan musician can tune each to a separate harmonic— thereby reinforcing not one but two pitches simultaneously, as sometimes occurs in the khöömei style.

ARTY-SAYIR (“the far side of a dry riverbed”) is a melody performed by throat-singer Vasili Chazir. The numbers identify the harmonic relative to the fundamental, transcribed here as a sustained low C note. The actual performance, available at www.sciam.com/ 1999/0999issue/0999levin.html, is about a semitone lower.

The third approach entails movement in the throat rather than in the mouth. For lower harmonics, vocalists place the base of the tongue near the rear of the throat. For mid-to-high harmonics, they move the base of the tongue forward until a gap appears in the vallecula—the space between the rear of the tongue and the epiglottis (the flap of cartilage that prevents food from entering the lungs). For the highest harmonics, the epiglottis swings forward to close the vallecula

In the fourth method, vocalists widen the mouth in precise increments. The acoustical effect is to shorten the vocal tract, raising the frequency of the first formant. The uppermost harmonic that can be reinforced is limited primarily by radiation losses, which worsen as the mouth widens. Depending on the pitch of the fundamental, a singer can isolate up to the 12th harmonic. Tuvans com- bine this technique with a second vocal source to create the kargyraa style, in which one may reinforce harmonics as unbelievably high as the 43rd harmonic.

Two Voices.

This additional source is another fascinating aspect of throat-singing. Singers draw on organs other than the vocal folds to generate a second raw sound, typically at what seems like an impossibly low pitch. Many such organs are available throughout the vocal tract. Kargyraa utilizes flexible

structures above the vocal folds: the so-called false folds (paired tissues that occur directly above the true folds and are also capable of closing the airstream); arytenoid cartilages (which sit in the rear of the throat and, by rotating side to side and back and forth, help to control phonation); aryepiglottic folds (tissue that connects the arytenoids and the epiglottis); and the epiglottic root (the lower part of the epiglottic cartilage). A different technique, which produces much the same sound but probably does not figure in kargyraa, combines a normal glottal pitch with the low- frequency, pulse like vibration known as vocal fry.

TWICE AS MANY TONES are available to a vocalist when he or she switches from normal song (left) to the kargyraa style of throat-singing (right). The vocal folds continue to intone a fundamental on the F note near 176 hertz, while the singer’s so- called false folds also come into play, producing a low F at half the frequency.

Because kargyraa resembles the sound of Tibetan Buddhist chant, some researchers have used the term “chant mode” to describe it. It generally, though not always, assumes a 2:1 frequency ra- tio, with supraglottal closure at every other vocal-fold closure. A typical fundamental pitch would be the C at 130.8 hertz, with the false folds vibrating one octave below at 65.4 hertz. Spectral analysis shows that when a singer switches into chant mode, the number of frequency components doubles, verifying that the second source is periodic and half the normal pitch. Chant mode also affects the resonant properties of the vocal tract. Because use of the false folds shortens the vocal tract by one centimetre (about half an inch), formant frequencies shift higher or lower depending on the location of the constriction on the selected formant.

Engrossing as all these vocal techniques are, Tuvan interest in throat- singing also focuses on the expressive sound world that it opens. As in every culture, music embodies a set of individual and social preferences as well as physical abilities. For example, in the seven-note scale between the sixth and 12th harmonics—the segment of the spectrum used by Tuvan and Mongolian singers—performers scrupulously avoid the seventh and 11th harmonics, because the local musical syntax favours pentatonic (five-tone) melodies, like that of the hymn “Amazing Grace.”

Another cultural preference is for extended pauses between breaths of throat- singing. (These breaths may last as long as 30 seconds.) To a Western listener, the pauses seem unmusically long, impeding the flow of successive melodic phrases. But Tuvan musicians do not conceive of phrases as constituting a unitary piece of music. Rather each phrase conveys an independent sonic image. The long pauses provide singers with time to listen to the ambient sounds and to formulate a response—as well as, of course, to catch their breath.

The stylistic variations all reflect the core aesthetic idea of sound mimesis. And throat-singing is just one means used by

herder-hunters to interact with their natural acoustic environment.

Tuvans employ a range of vocalizations to imitate the calls and cries of wild and domestic animals. They play such instruments as the ediski, a single reed de- signed to mimic a female musk deer; khirlee, a thin piece of wood that is spun like a propeller to emulate the sound of wind; amyrga, a hunting horn used to approximate the mating call of a stag; and chadagan, a zither that sings in the wind when Tuvan herders place it on the roofs of their yurts. Players of the khomus, or jew’s harp, re-create not only natural sounds, like that of moving or dripping water, but also human sounds, including speech itself. Good khomus players can encode texts that an experienced listener can decode.