Experimental research on overtone singing : Hugo Zemp et Trân Quang Hai

Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles Vol. 4, voix (1991), pp. 27-68 (42 pages) Published By: Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie

1 This research was carried out within the framework of the Propre Research Unit nº 165 of the CNRS, in the Department of Ethnomusicology of the Musée de l’Homme. Before sending the final manuscript to the publisher, we were able to present a summary of our work at the UPR seminar. The questions and remarks helped us to correct and clarify our analysis. Gilles Léothaud and Gilbert Rouget then befriended us to re-read the manuscript and share their suggestions for improving it.

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone.

return to various khöömii papers main page.

The term “overtone singing” refers to a singular vocal technique in which a single person sings in two voices: a drone formed by the fundamental sound, and a superimposed melody formed by harmonics.

This article is the result of two complementary approaches: a pragmatic research through the learning and exercise of overtone singing that Trân Quang Hai has been carrying out since 1971, and a visualization research conducted on the physiological and acoustic level for the preparation and production of the film Le chant des harmoniques, directed by Hugo Zemp in 1988-89. In this film, Trân Quang Hai is the main actor, alternately singer and ethnomusicologist: teaching overtone singing during a workshop, interviewing Mongolian singers, lending himself to radiocinematography with computer image processing, and singing into the spectrograph’s microphone to then analyze his own vocal technique (2). The spectrographic images that we discovered practically at the same time as we were filming them – the latest Sona-Graph model allowing the analysis of the sound spectrum in real time and it synchronously had arrived at the Department of Ethnomusicology of the Musée de l’Homme a few days before shooting – encouraged us to pursue these investigations and to lead them in a direction that we would probably not have envisaged without the making of the film (3).

2 The details of the making of this film – which premiered on July 27, 1989 at the Congress of the International Council for Traditional Music in Schladming (Austria) – are described elsewhere (cf. Zemp 1989). A booklet, to accompany the edition in the form of a videocassette, is currently in preparation.

3 Research carried out in close collaboration by the two co-authors who each made – in addition to the joint evaluation of each stage of the work – specific contributions. The sonograms, as well as the detailed analyzes used to write the legends of the figures, are from Trân Quang Hai who, moreover, is at the same time “privileged informant” and singer of 26 recordings reproduced on sonograms. The research design, formatting and writing of the article is by Hugo Zemp.

The use of spectrographic tools for the analysis of overtone songs is not new: Leipp (1971), Hamayon (1973), Walcott (1974), Borel-Maisonny and Castellengo (1976), Trân Quang Hai and Guillou (1980 ), Gunji (1980), Harvilahti (1983), Harvilahti and Kaskinen (1983), Desjacques (1988), Léothaud (1989). There is no question, within the framework of this article, of evaluating this work, of summarizing its results or of giving its history. In the most recent study, G. Léothaud (1989: 20-21) (4) summarizes excellently what he calls the “acoustic genesis of overtone singing”.

4 Appeared in a new publication: Dossier nº 1 of the Institut de la Voix, Limoges. In addition to two brief reports relating to clinical and paraclinical examinations of the phonatory apparatus and the overtone emission of Trân Quang Hai, examinations carried out one by an O.R.L. (Sauvage 1989) and the other by a phoniatrist (Pailler 1989), and an extract from a presentation on the realization of overtone singing (Trân Quang Hai 1989), this file also contains the most complete bibliography and discography to this day concerning overtone singing.

The phonatory apparatus, like any musical instrument, is made up of an exciting system, here the larynx, and a vibrating body responsible for transforming the energy received into acoustic radiation, the pharyngo-buccal duct.

The larynx delivers a harmonic spectrum, the primary laryngeal sound, determined in frequency, of homogeneous appearance, that is to say devoid of notable formants – therefore of vocalic color – and whose richness in harmonics varies essentially according to the vibratory structure of the vocal cords […].

This primary supply passes through the pharyngo-buccal cavities, undergoing significant distortions there: the pharynx and the mouth therefore behave like Helmholtz resonators, and this for all frequencies whose wavelength is greater than the largest dimension of these cavities. […].

The parameters determining the natural frequency of the phonatory cavities can vary in considerable proportions thanks to the articulator system, in particular by the mobility of the jaw, the opening of the mouth and the position of the tongue. This, above all, can divide the oral cavity into two resonators of smaller volume, therefore of higher natural frequency. In other words, the oral cavities can continue to behave as Helmholtz resonators even for very high harmonics of the laryngeal spectrum, those whose wavelength is small, and in any case less than the length of the pharyngo-pharyngeal duct. oral.

Overtone emission consists for the singer of emitting a spectrum rich in harmonics, then very finely tuning a phonatory cavity to one of the components of this spectrum, the amplitude of which thus increases sharply by resonance; by moving the tongue, the oral volume can vary, therefore the natural frequency, and in this way select different harmonics.

It proposes an analysis grid, centered on four levels and twelve relevant criteria. 1º Characteristics of the voice spectrum; 2º Nature of the overtone formant; 3º Characteristics of the melody of harmonics; 4º Field of freedom of diphonic fluctuation. The application of this grid makes it possible to deepen and systematize the spectral analysis of overtone singing which can now be based on many new sound documents recently published on discs, adding to the well-known old ones. However, that is not our goal.

We propose to examine how the different styles or stylistic variants of overtone singing – called among the Mongols khöömii (5) (“pharynx, throat”) and among the Tuva of the USSR khomei (from the Mongolian term) – are physiologically produced . In this field, the descriptions are rare and not very detailed, whereas we have known for many years the vernacular names designating these styles among the Tuva, whom Aksenov (1973: 12) thinks form the center of the Turco-Mongolian culture. overtone singing, since they practice not just one but four stylistic variants (kargiraa, borbannadir, sigit, ezengileer; a fifth name, khomei which is at the same time the generic name of overtone singing, replacing in some places the term borbannadir) . Implicitly, the neighboring peoples he cites – Mongols, Oirats, Kharkass, Gorno-Altais and Bashkirs – would know only one style. In any case, for the Mongols and for the Altai of the USSR, mountain dwellers living in the chain of the same name, this is not correct. The latter use three styles named on the notice of a record sibiski, karkira, kiomioi (Petrov and Tikhonurov). The most famous overtone singer in Mongolia and abroad, D. Sundui, listed five styles during the Musical Voices of Asia festival in Japan: xarkiraa xöömij (narrative xöömij), xamrijn xöömij (nose xöömij), bagalzuurijn xöömij ( throat xöömij), tseedznii xöömij (chest xöömij), kevliin xöömij (belly xöömij), the last two being generally not differentiated (Emmert and Minegishi 1980: 48). In the interview for the film Le chant des harmoniques, T. Ganbold indicates the same five names. He briefly introduces the first four styles, adding that he does not know how to do “belly khöömii”, thereby distinguishing it from “breast khöömii”. But he does not explain how he produces these different styles. It is true that the interview had to be done in a very short time, saving film, and with the help of a translator, an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, probably unfamiliar with the subtleties of singing. . T. Ganbold and G. Iavgaan had also led several workshops at the Maison des cultures du monde in Paris; this time the translation was provided by an ethnomusicologist, Alain Desjacques, but the two singers were not more explicit. As for D. Sundui, to whom a Japanese musicologist asked how to learn overtone singing, he replied simply that you had to know how to hold your breath as long as possible, use it effectively, then listen to sound recordings and try (Emmert and Minegushi 1980: 49).

5 The transliteration changes according to the authors xöömij, khöömii, chöömij, ho-mi.

Despite the fact that his country of origin (Vietnam) and his host country (France) do not traditionally know overtone singing – or perhaps because of it – Trân Quang Hai succeeds in reproducing different styles or stylistic variants , or at least come close. Having learned without receiving instructions or advice from experienced singers, and without being able to rely on published descriptions, he was forced to proceed by trial and error. This empirical, but nevertheless systematic research, allowed him to become aware of what is happening at the level of the oral cavity. Conducting introductory workshops on overtone singing for many years has led him to know how to explain it.

The originality of the new research presented here consists of 3 points:

1. Trân Quang Hai tries to imitate as best as possible the songs reproduced on the sound recordings we have. For this, he relies on both auditory and visual perception, trying to obtain, on the Sona-Graph monitor, tracings of spectra similar to those of singers from Mongolia, Siberia, Rajasthan and from South Africa.

2. He subjectively describes what he does and feels physiologically when he gets these tracings.

3. In order to better understand the mechanism of the different styles and to explore all their possibilities – even if they are not exploited in traditional overtone singing – he performs experiments that no one has probably ever tried.

This research could not be carried out with old-fashioned spectrographs used until 1989 by the authors mentioned above. This required a device capable of restoring the sound spectrum in real time and synchronous sound, the DSP Sona-Graph Model 5500 that our research team acquired in December 1988. If we change, while singing, the parameters of the vocal emission, we immediately see the layout of the harmonics change. Thanks to the feedback of the new tracing, the voice output can again be changed. Thus, the research is strictly experimental. In the first study on the acoustics of overtone singing, E. Leipp reproduces a theoretical diagram of the phonatory apparatus, showing five main cavities as resonators: 1º the pharyngeal cavity; 2º the posterior oral cavity; 3º the anterior oral cavity, the tip of the tongue directed towards the palate separating cavities 2 and 3; 4º the cavity between the teeth and the lips; 5º the nasal cavity (Leipp 1971). The exact role of these different cavities seems difficult to define.

Thanks to his pragmatic experience as a singer and pedagogue, Trân Quang Hai was led to distinguish two basic techniques essentially using one oral cavity or two oral cavities (Trân and Guillou 1980: 171), the two techniques being able to be more or less nasalized . In the one cavity technique, the tip of the tongue stays down, like when pronouncing vowels. Trân Quang Hai found this technique perfect to make beginners feel better the modification of the buccal volume with the pronunciation of vowels. He tells the trainees that they must “leave the tongue in a resting position” (cf. the film Le chant des harmoniques). The X-ray images from the film, however, show that the back of the tongue rises during the successive pronunciation of the vowels o, ɔ, a (this is not related to overtone singing). Radiologist F. Besse speaks of “the ascent of the tongue”. The “tongue rest” metaphor still holds true in the sense that the tip of the tongue stays down. The radiological image shows that in this technique there is contact between the soft palate and the posterior part of the tongue, separating the oral cavity from the pharyngeal area.

In the two-cavity technique, the tip of the tongue is applied against the roof of the palate, thus dividing the oral volume into an anterior cavity and a posterior cavity. Here there is no contact between the back of the tongue and the soft palate; the posterior buccal cavity and the pharyngeal cavity being connected by a wide passage. The selection of different harmonics to create a melody can be done in two ways: a) the tip of the tongue moves from back to front, with the highest harmonic being obtained in the most forward position; the anterior oral cavity is then reduced to the maximum (cf. the radiological images of the film Le chant des harmoniques); b) the tip of the tongue remains glued to the palate without moving, the harmonics being selected according to the greater or lesser opening of the lips: from the smallest opening when pronouncing the vowel o (Low harmonic) until ‘at the widest opening when pronouncing the vowel i (high harmonic). This second way does not seem to be used by the Mongolian singers that we have been able to observe, and Trân Quang Hai only uses it for its pedagogical interest (comparison with the one-cavity technique) during his initiation workshops.

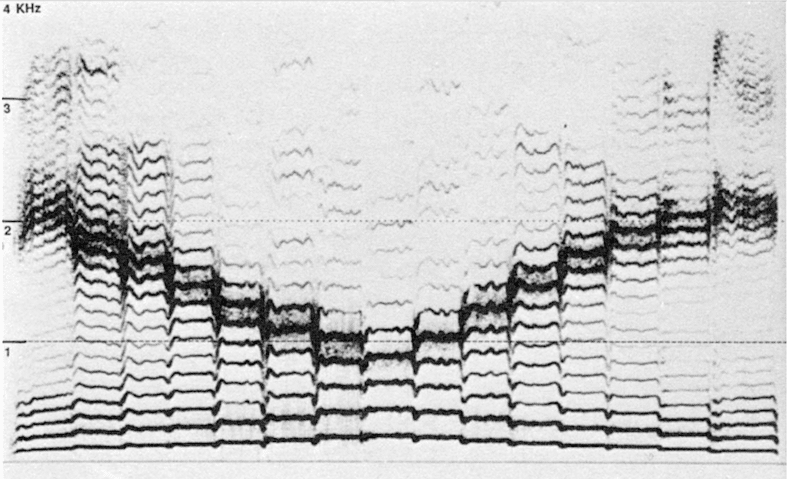

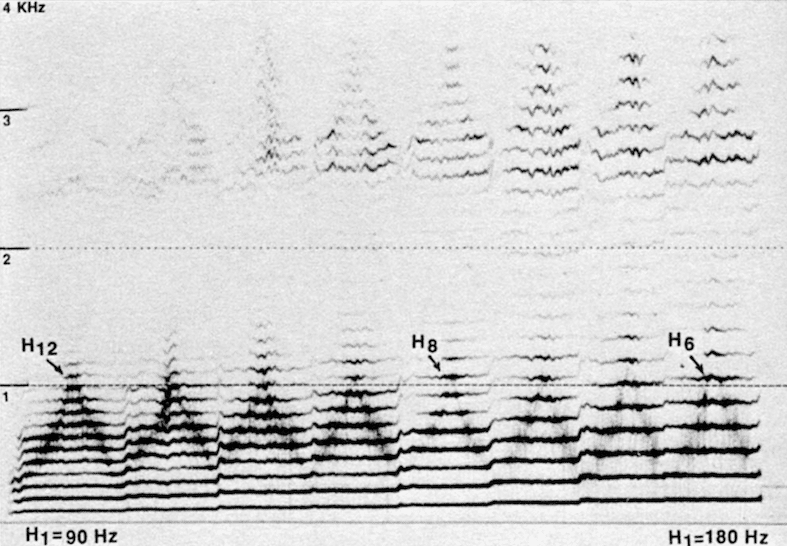

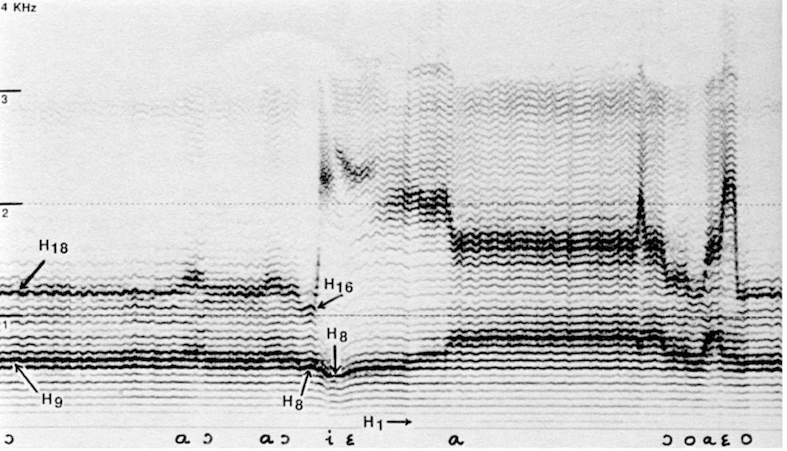

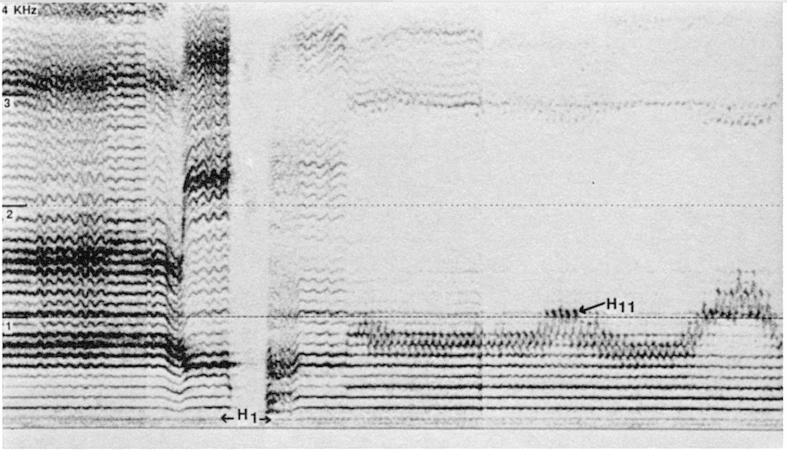

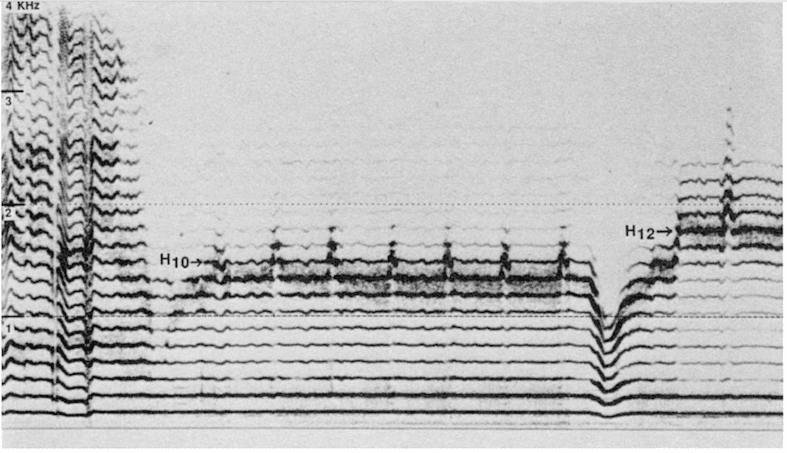

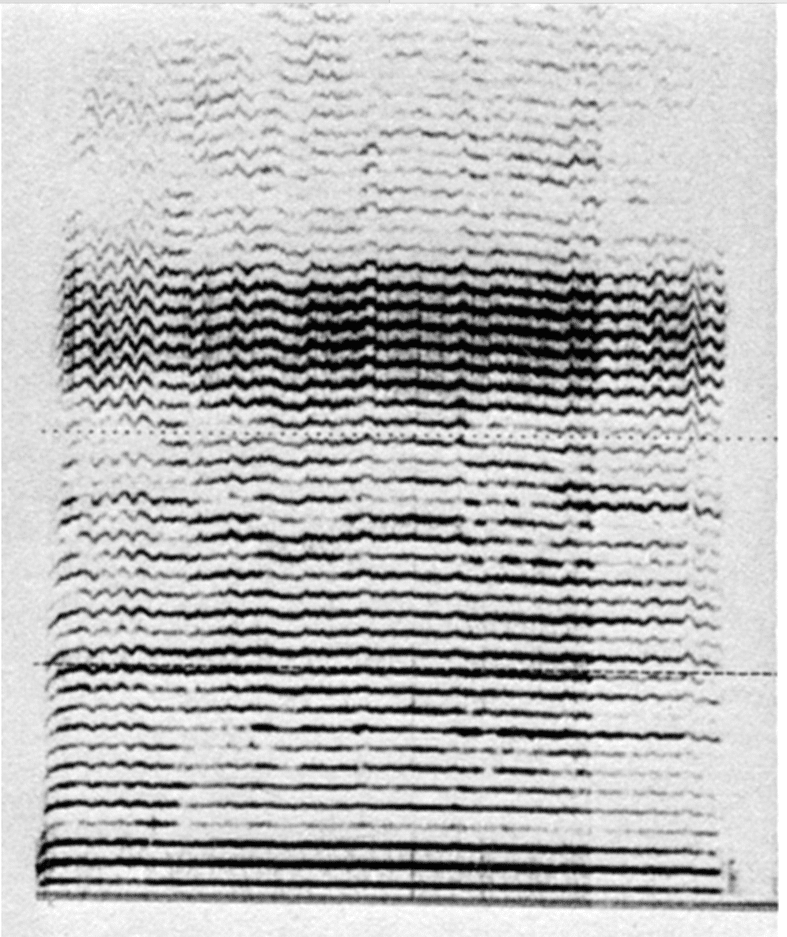

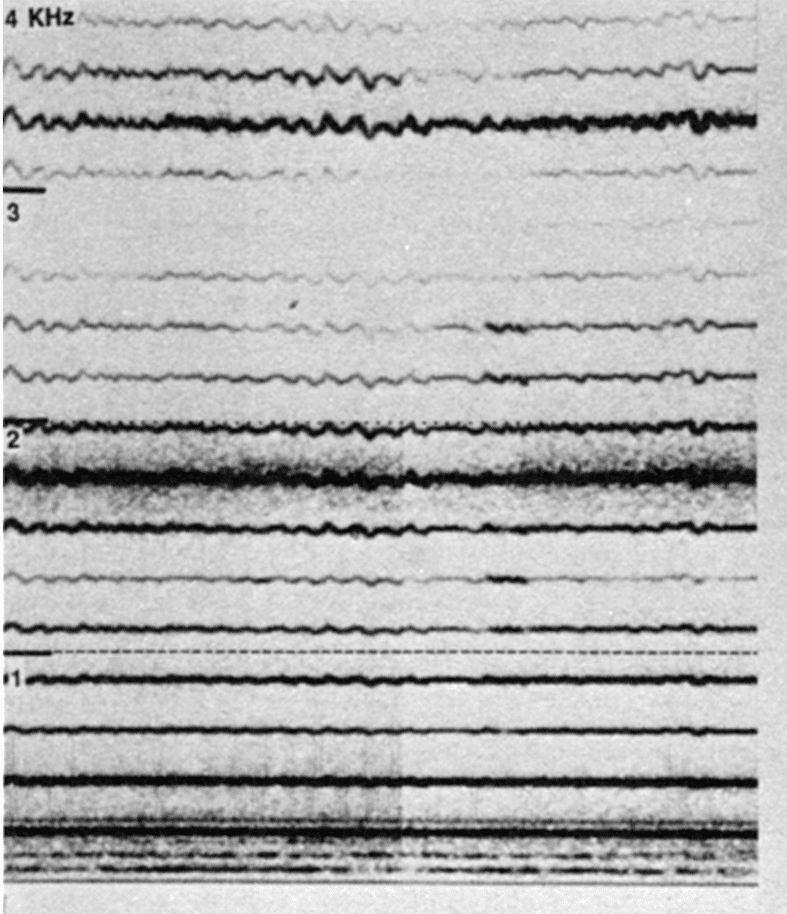

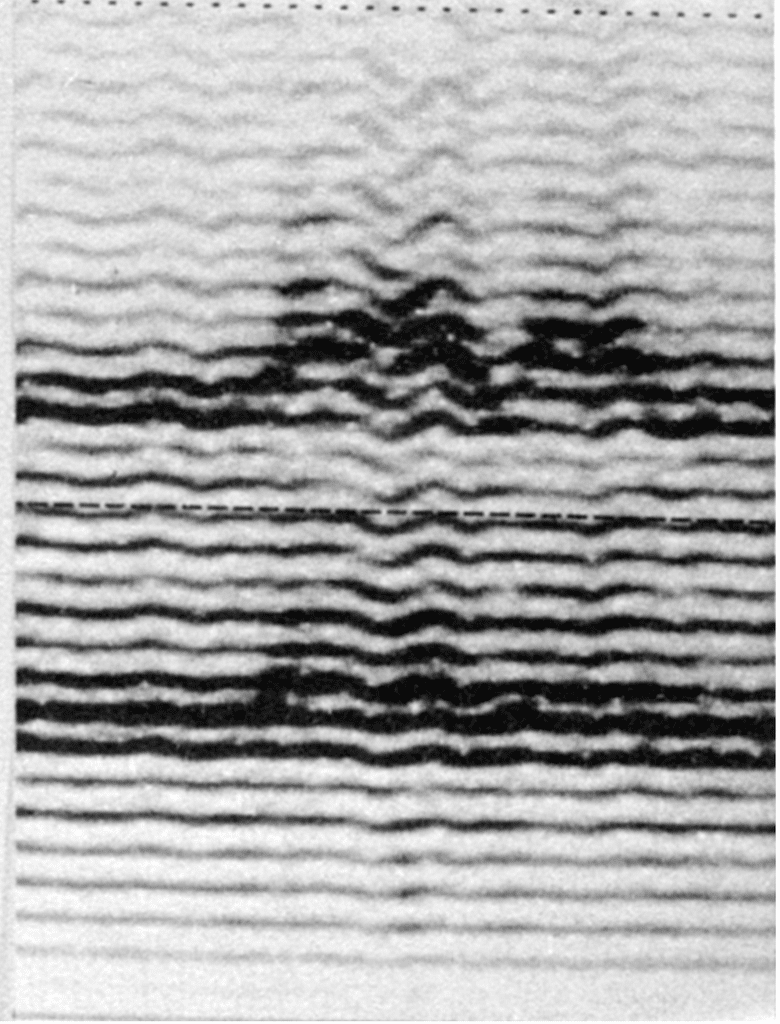

In order to explore all the possibilities of the two main techniques, Hai sang harmonic scales from different pitches of the fundamental. For the one-cavity technique, we see in Figure 1 that the harmonics that can be used to create a melody only slightly exceed the upper limit of 1000 Hz, whatever the fundamental. But the lower the fundamental, the more harmonics there are. Thus, for the lowest fundamental (90 Hz, approximately one fa1) of fig. 1, usable harmonics are H4 (360 Hz), 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 (1080 Hz), resulting in the scale (transposed) C, E, G, B♭ – , do, re, mi, fa#-, sol. For the highest fundamental (180 Hz) of fig. 1, only harmonics 3, 4, 5 and 6 are exploitable, and the resulting scale, sol, do, mi, sol, is much poorer in melodic possibilities.

With the two-cavity technique (fig. 2), and the lowest fundamental (110 Hz = A1), Trân Quang Hai manages to bring out the harmonics between H6 (660 Hz) and H20 (2200 Hz). To create a melody in the highest zone, it is necessary to select even or odd harmonics (see below fig. 11 and 12), since the harmonics are too close together for a musical scale. The transmission of the highest fundamental (220 Hz) of fig. 2 selects from H4 (880 Hz) to H10 (2200 Hz).

A quick glance shows that, in fact, the harmonics obtained by the one-cavity technique are essentially located in a zone up to 1 KHz, whereas the harmonics obtained by the two-cavity technique are placed mainly in the area from 1 to 2 KHz.

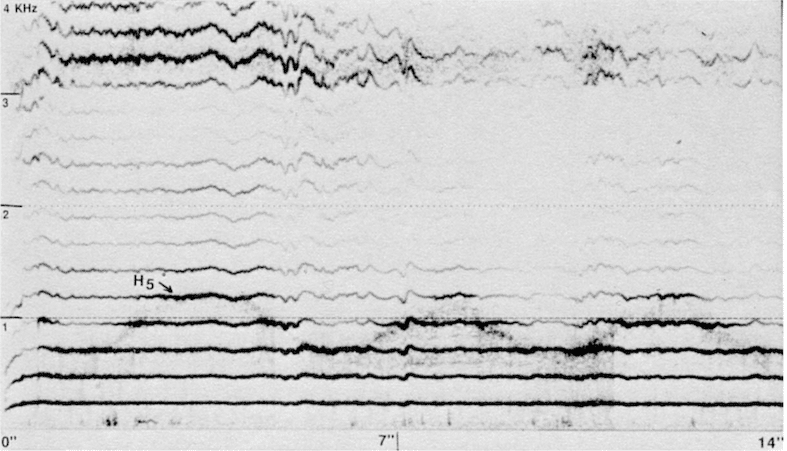

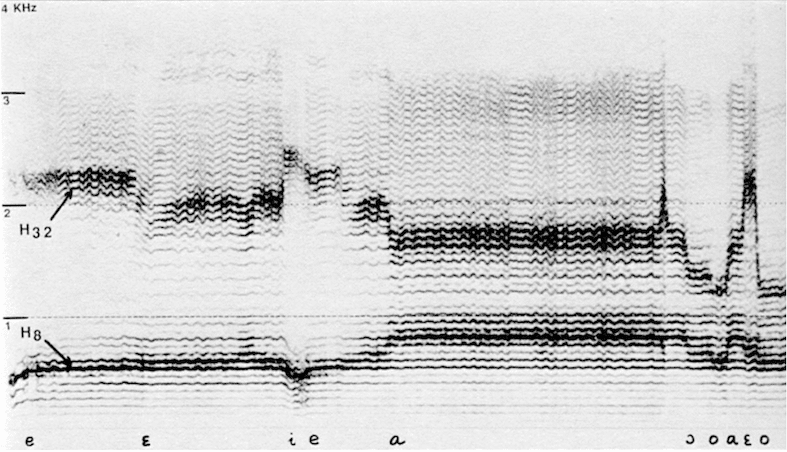

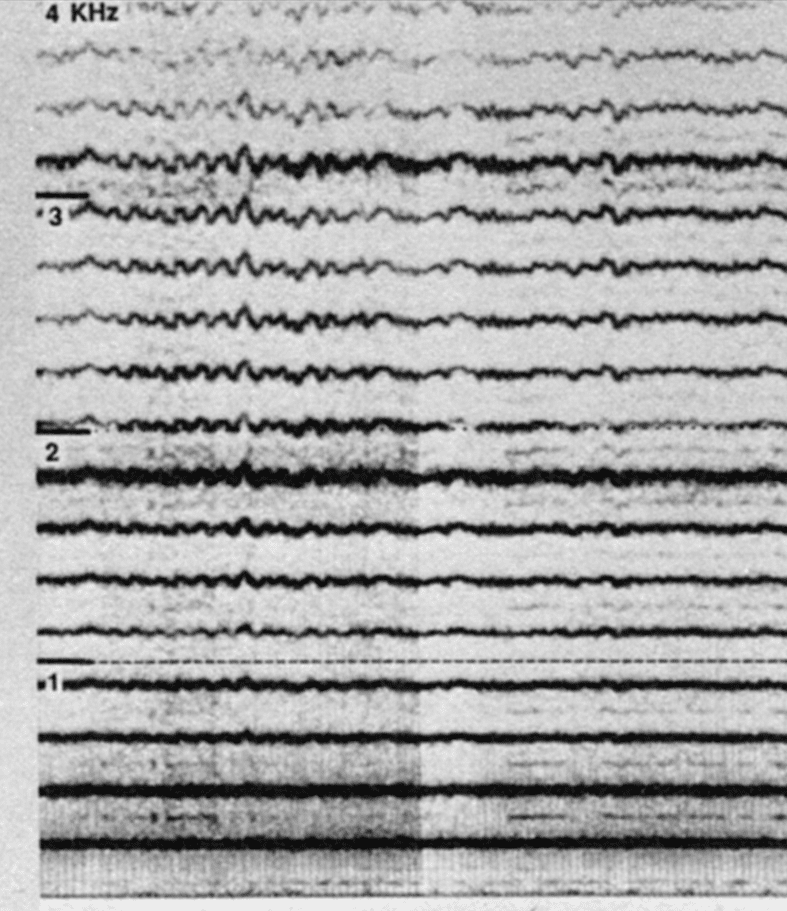

Traditionally, Mongol and Tuva women did not practice overtone singing. According to the singer D. Sundui, this practice would require too much force, but there would be no prohibition on this subject among the Mongols (Emmert and Minegushi 1980: 48). Among the Tuva of the Soviet Union, overtone singing is said to be almost exclusively reserved for men; a taboo based on the belief that it would cause infertility to the woman who practiced it would gradually be abandoned, and some young girls would now learn of it (Alekseev, Kirgiz and Levin 1990). These authors further say that “women are able to produce the same sounds, albeit at higher pitches”, which is only partially true. It’s true if we talk about the “sounds” of the drone which are higher for a female voice than for a male voice, but it’s not true for the melody of harmonics which cannot go higher than in men. This can already be deduced by examining Figs. 1 and 2 where the upper limit of harmonics obtained from the highest fundamental (180 and 220 Hz) is not higher than the upper limit of harmonics obtained from the lowest fundamental, one octave lower (90 and 110Hz). Confirmation can be found by examining Figs. 3 and 4, reproducing the voice of Minh-Tâm, the daughter of Trân Quang Hai (6). With the technique with one cavity and a fundamental of 240 Hz, the number of harmonics is very limited H3 to H5 (1200 Hz). With the two-cavity technique and a 270 Hz fundamental, harmonics 4 (1080 Hz) to 8 (2160 Hz) can be used to create a melody, resulting in a richer scale (transposed C, E, G, B ♭-, C). It follows that a high-pitched woman’s voice does not allow melodies to be created using the single-cavity technique. The Xhosa woman from South Africa recorded by R.P. Dargie, who however uses this technique (as shown in Figs. 7 and 8), has a deep voice, in the register of male voices (100 and 110 Hz = G1 and A1).

6 She was seventeen when this recording was made, but her father had taught her overtone singing from the age of six.

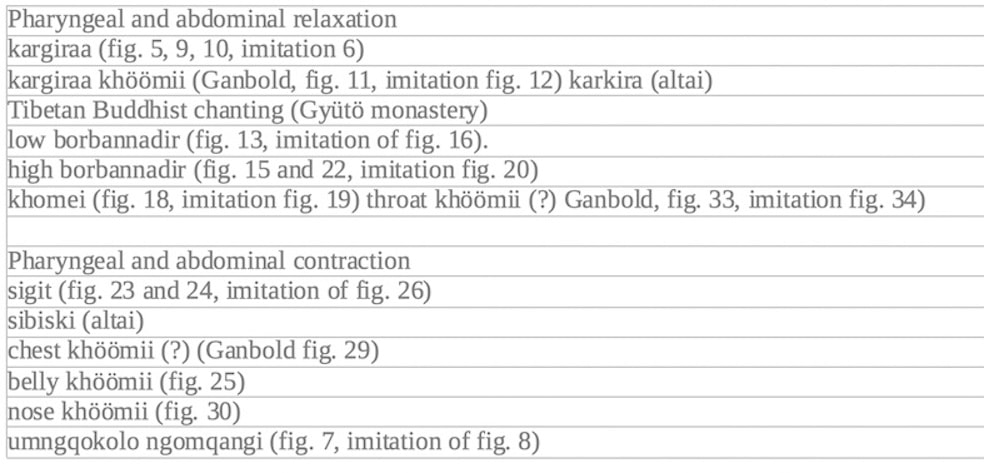

If the conclusions that we have drawn from these experiments (fig. 1 to 4) are correct – and we believe that they are – we should be able to deduce that the styles of overtone singing whose sonograms present a melody of harmonics do not not exceeding essentially 1 KHz are obtained according to the one-cavity technique, while those whose melody of harmonics lies essentially between 1 and 2 KHz are obtained according to the two-cavity technique. The experiments made by Trân Quang Hai, trying to imitate the different stylistic variants, confirm this. In the lines that follow, we will examine the physiological characteristics of the different stylistic variants of overtone singing, identifying three criteria: the resonator(s); muscle contractions; ornamental processes.

G. YAVGAAN. Frame taken from the film

“Le chant des harmoniques” by H. Zemp.

T. GANBOLD. Frame taken from the film

“Le chant des harmoniques” by H. Zemp.

The resonator(s).

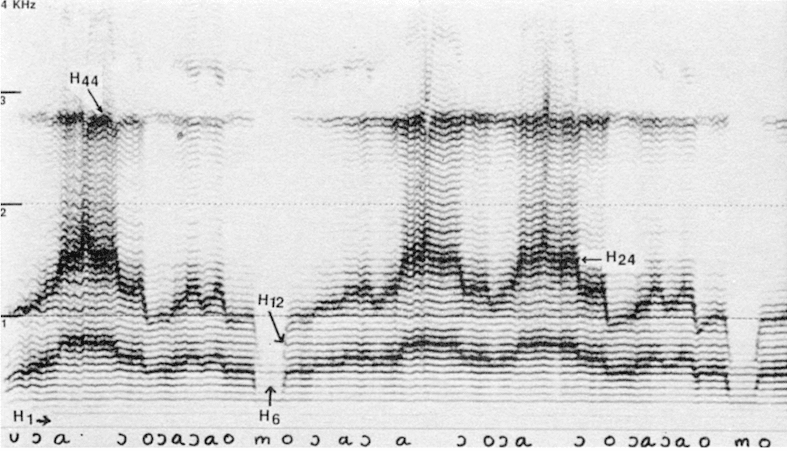

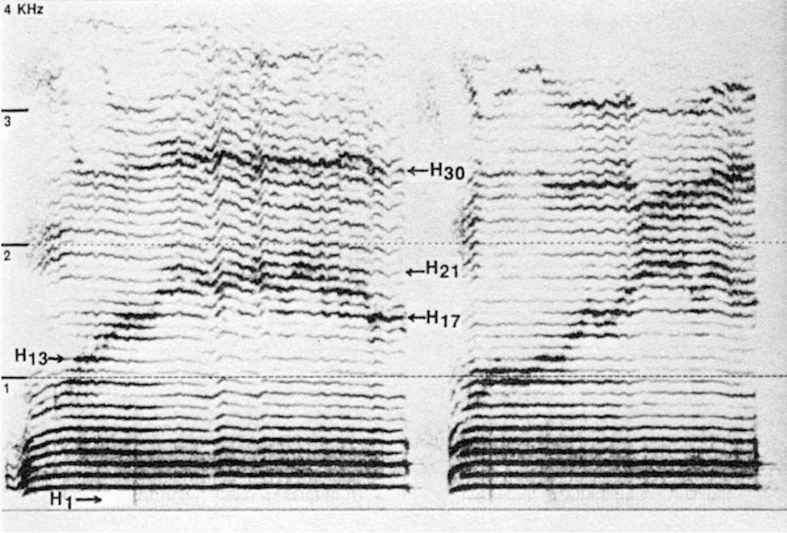

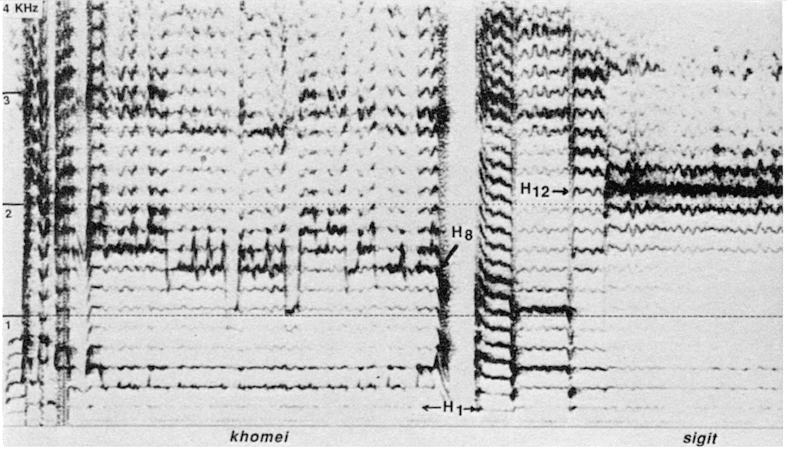

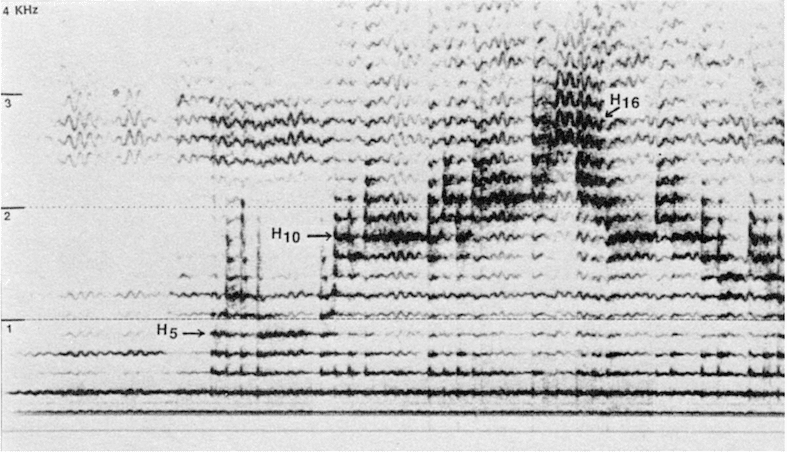

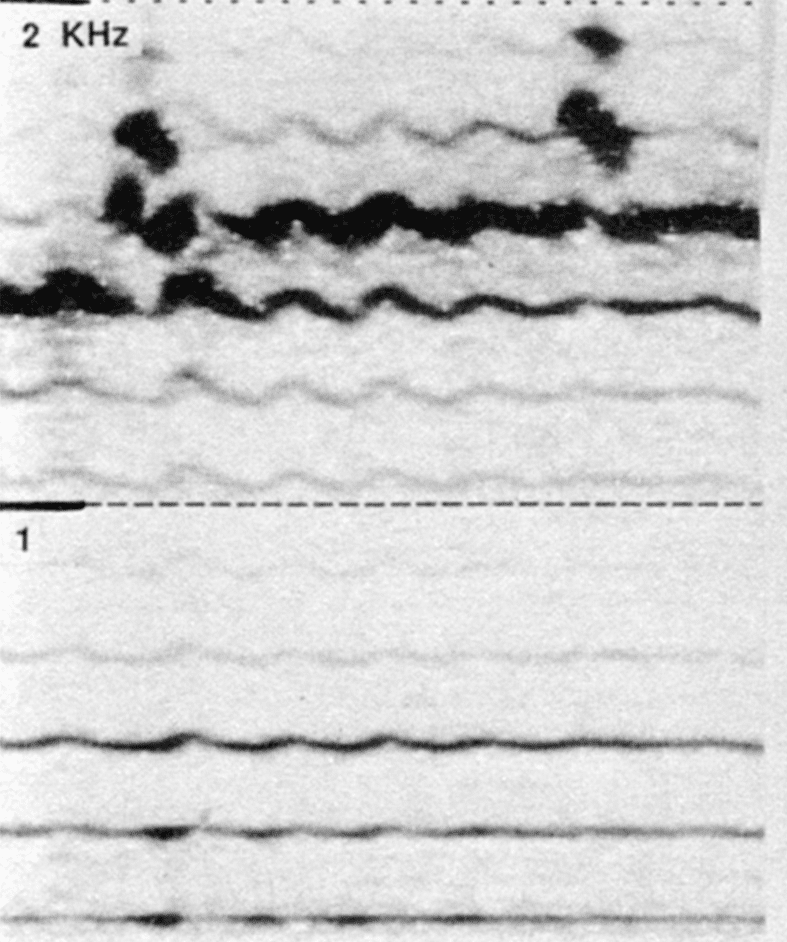

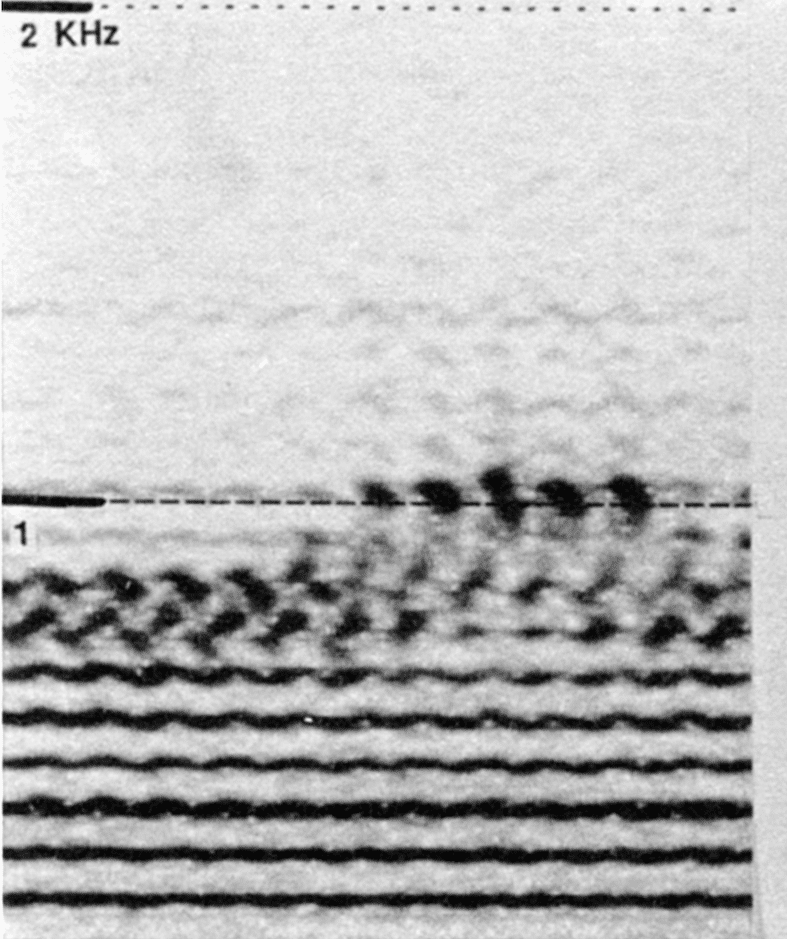

According to Aksenov, the kargiraa style of the Tuvans is characterized by a low fundamental located on one of the four lowest degrees of the great octave, and which can drop down a minor third for a short time. The melodic change from one harmonic to another is accompanied by a change in vowels (Aksenov 1973: 13). The two songs reproduced here (fig. 5, 9 and 10) have fundamentals of 62 Hz and 67 Hz (momentarily 57 Hz). The melody of harmonics reaches in the first case 750 Hz (H12), in the second case 804 Hz (H12) (7). Above the melody of harmonics we see a second zone, at the octave when the back vowels are pronounced (fig. 5 and 9), or higher with the front vowels (fig. 10) (8). By imitating the plot of Fig. 5, Trân Quang Hai uses the one-cavity technique, half-open mouth; unlike the tuva songs, the harmonic melody is broadband, and H1 is very pronounced (fig. 6). All the seven recordings identified on the records of the discs as belonging to the style kargiraa among the Tuvans and karkira among the Altains have been verified with Sona-Graph (9). The fundamental frequency is between 62 and 95 Hz; the harmonic melodies of all the rooms without exception are below 1 KHz.

7 According to Alekseev, Kirgiz and Levin (1990), the piece that we have represented in figs. 9 and 10 is a variant of the kargiraa, called “Steppe kargiraa”, and recalls the tantric chants of Tibetan monks. For our part, we did not notice any difference with the other tuvan kargiraa style pieces, and the very characteristic melody of harmonics has only few elements in common with the harmonics which appear in the Tibetan songs of the monasteries. Gyüto and Gyüme.

8 The harmonics of this second zone undoubtedly enrich the timbre, but they are not perceived by the ear as forming a melody separate from the melody of harmonics of the first zone.

Folkways/Smithsonian Nos. 1, 8, 9, 17, 18. Melodia, side A, track 9. Le Chant du Monde, side A, track 5.

It is only since the recent work on the music of the Xhosa people of South Africa carried out by R.P. Dargie (1989), and the recordings he entrusted in 1984 to Trân Quang Hai for the sound archives of the Museum of Man, that we know of the existence of overtone singing practiced far from Central Asia. The piece sung by a Xhosa woman (fig. 7), characterized by the alternation of two fundamentals of 100 and 110 Hz and a melody of harmonics not exceeding 600 Hz, is probably made using the single-cavity technique. , as shown by the imitation of Trân Quang Hai, however imperfect it may be (fig. 8).

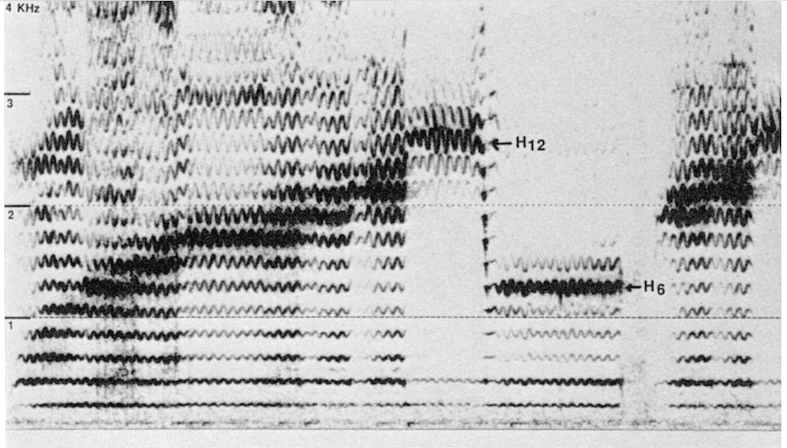

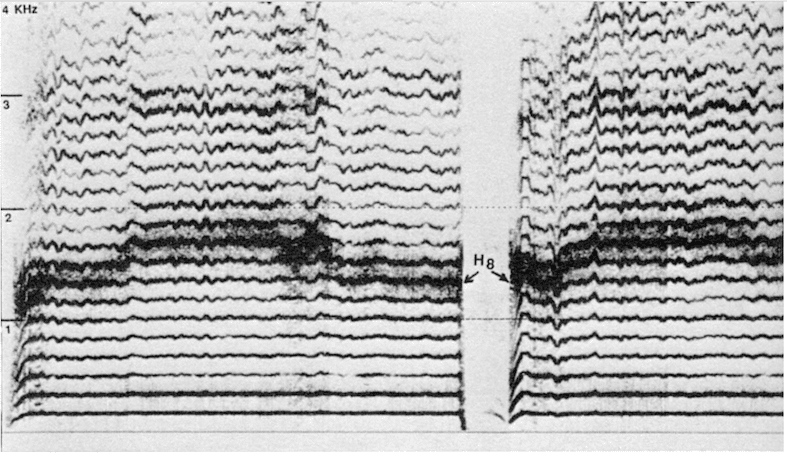

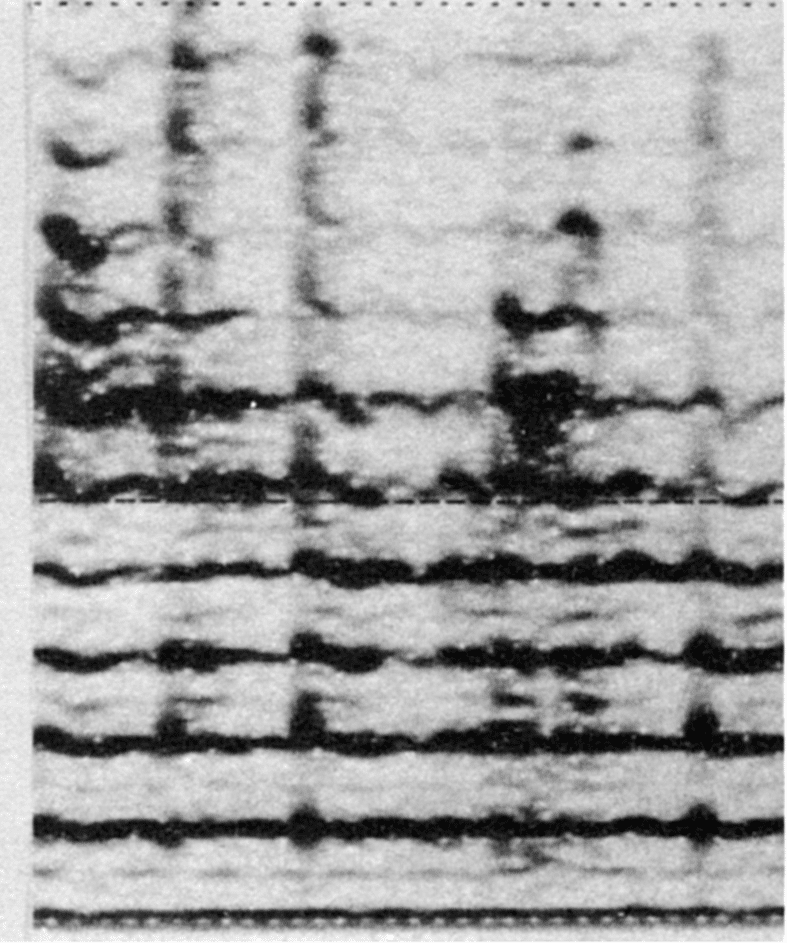

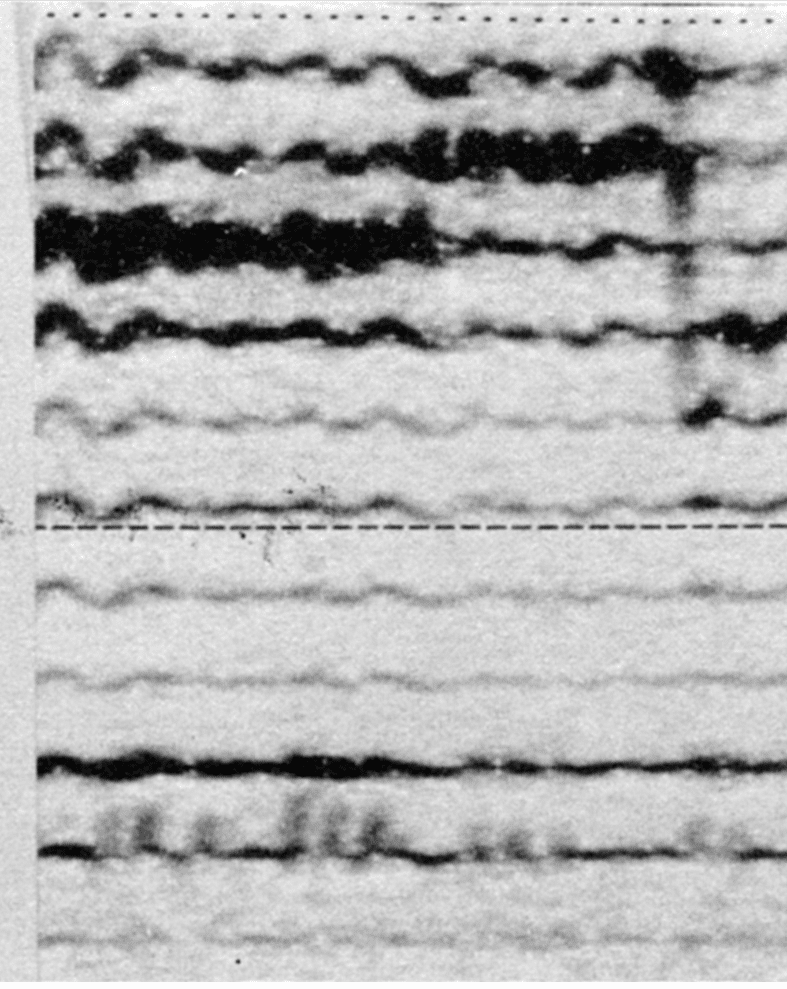

What about the style kargiraa khöömii (10) of the Mongolian singer T. Ganbold (fig. 11), whose sonogram we have deliberately placed in front of tuvan kargiraa (fig. 9 and 10)? The fundamental is low (85 Hz) and not very marked as in the tuva pieces, but the harmonic melody is in the 1 to 2 KHz zone and not below 1 KHz. To obtain a similar line, Trân Quang Hai had to use the two-cavity technique. How can this difference from the equivalent style among the Tuvans be explained? When the Ensemble de Danses et de Chants de la R.P. de Mongolie arrived in Paris, the Embassy of Mongolia organized a reception which we had the honor and the pleasure of attending. Like other artists in the troupe, T. Ganbold was demonstrating his art there, and we thought it would be interesting to include in our film the piece he had composed, “Liaisons de khöömii”, to introduce the public to three stylistic variants of overtone singing (11). The piece did not appear in the concert program at the Maison des Cultures du Monde, because T. Ganbold, having composed it recently, had not yet mastered it completely. In agreement with the director of the troupe, he nevertheless agreed to sing it on stage outside the concert for the filming of the film, then during a concert, as an encore (so that we could film his entrance on stage as well as the applause) , and to give a short demonstration of the different styles during the interview. In the absence of recordings of other Mongolian singers, it cannot be said whether T. Ganbold got the technique wrong, or whether in Mongolia it is considered right to sing the kargiraa khöömi style according to the two-cavity technique. We can also consider that the borders between the different styles are not rigid, that the singers use the technical possibilities as they want (or can), that they use the denominations with more or less rigor. Among the Tuva also, as we will see in the following paragraph, the same denomination of style can designate songs performed according to the two different techniques.

10 The denomination xaarkiraa xöömij is “translated” in Emmert and Minegushi (1980 48) by “narrative xöömij”, no doubt to reflect the fact that in this style the overtone part can be preceded by a narrative part sung with the natural voice. In the film Le chant des harmoniques, the name kargiraa khöömii was translated by Alain Desjaques as “black crane khöömii”, khargiraa designating in Mongolian this bird whose deep and hoarse voice could have given the name to this style. Unless the Mongols borrowed the term kargiraa from the Tuva for whom, according to Alekseev, Kirgiz and Levin (1990), it comes from an onomatopoeic word meaning “to breathe painfully”, “to speak in a hoarse or hoarse voice”. We cannot decide between the two interpretations. It is also possible that some borrowed the term from others, while later finding a meaning in their own language.

11 This seems to be a recent phenomenon. According to Alekseev, Kirgiz and Levin (1990), tuva singers once specialized in one or two related styles, but today young people use several styles and frequently arrange melodic segments into polystylistic mixtures.

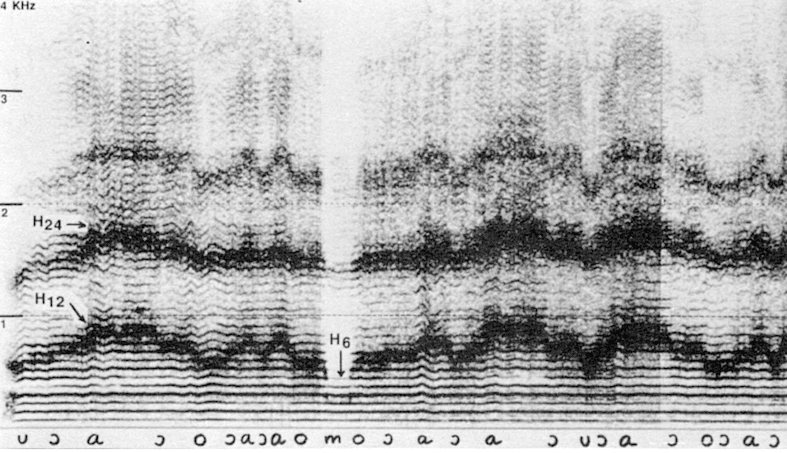

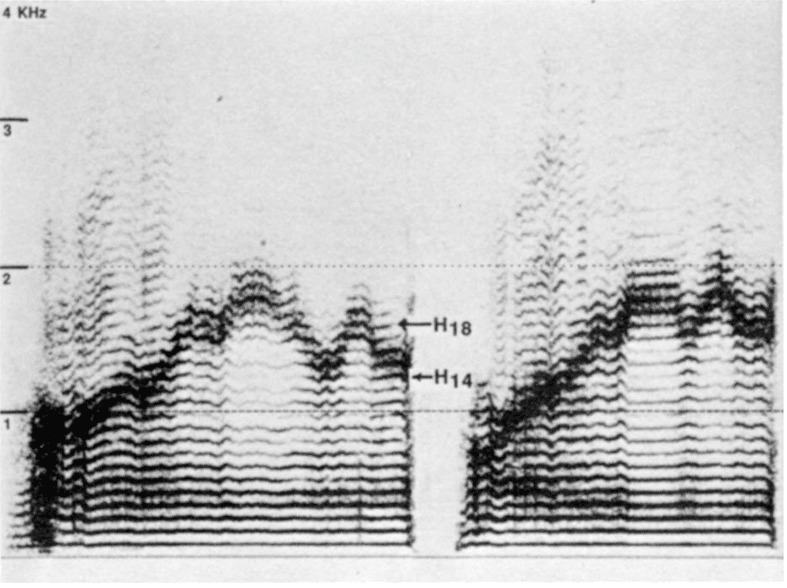

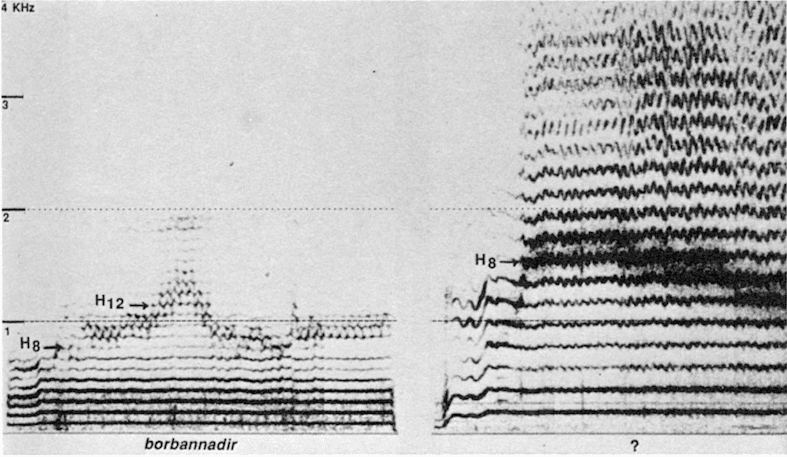

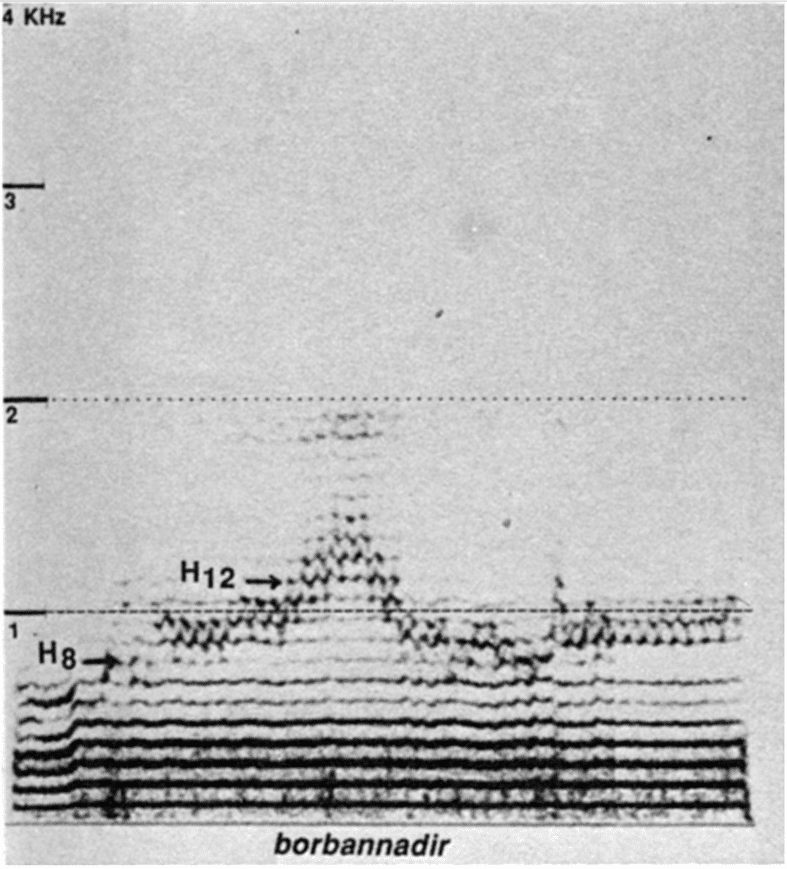

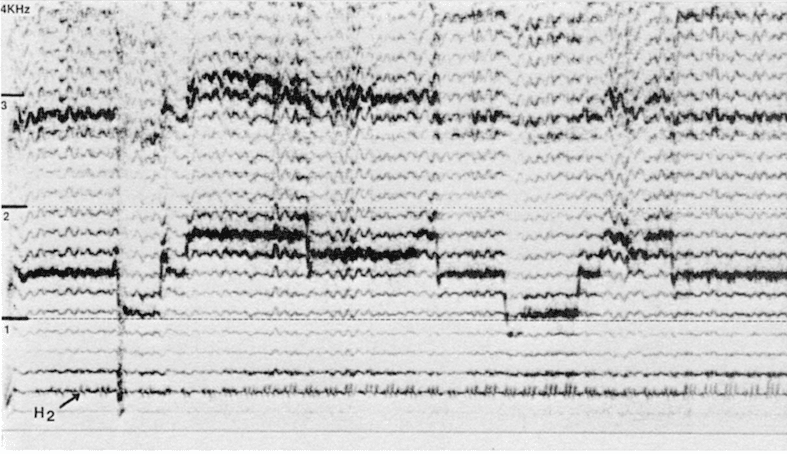

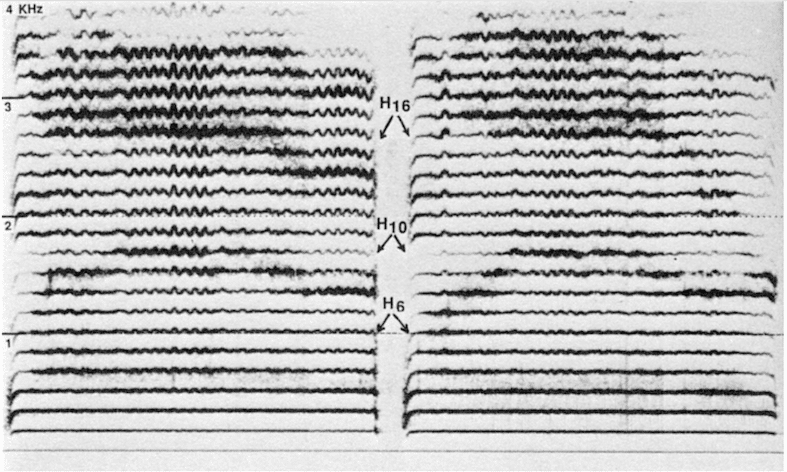

According to Aksenov, the tuvan borbannadir style is characterized by a slightly higher fundamental than that of the kargiraa, using one of the three degrees in the middle of the great octave. The lips are almost completely closed, the sound would be softer and resonant. The borbannadir style would be considered by the Tuvans to be technically similar to the kargiraa style, allowing a sudden change from one to the other within the same piece (1973: 14). Examination of the five pieces identified on the record notices as belonging to the Borbannadir style shows that in two pieces, the fundamental is at 75 and 95 Hz, and the melody of harmonics below 1 KHz (12) (cf. . 13). These two pieces are therefore very close to the kargiraa style, sung according to the single cavity technique. The other three borbannadir recordings have a higher fundamental (120, 170 and 180 Hz) and a melody of harmonics above 1 KHz, thus obtained by the two-cavity technique (13). We reproduce an example (fig. 15), and its imitation by Hai (fig. 16).

12 Folkways/Smithsonian, Nos. 11 and 14.

13 Melodia, side 1, track 5. Folkways/Smithsonian, nos. 12 and 13.

Sonagraphic analysis shows (but also simple listening) that in a recording called borbannadir by the authors of the record of the disc, and which we have already briefly mentioned (fig. 13), three styles are sung alternately. The extract on the left has all the characteristics of the kargiraa style, which is obviously followed, after a one-second interruption, by the borbannadir style with the same fundamental and the melody of harmonics below 1 KHz. The sonogram of fig. 14, showing another extract from the same recording, also presents on the left the kargiraa style, followed this time without interruption by a very short fragment (2 seconds) of borbannadir with the same fundamental. Then, after a short interruption, the fundamental makes an octave jump from 95 Hz to 190 Hz, and the melody of harmonics is located above 1 KHz, even exceeding 2 KHz in some places (see also the imitations of Hai, Fig. 16 and 17). Listening to and tracing the sonogram, this last part closely resembles the “belly khöömi” style of the Mongolian singer D. Sundui (fig. 20), and there is no doubt that it is sung according to the technique with two cavities.

According to Aksenov, in some Tuvan areas, the name khomei replaces the name borbannadir. Among the six examples of tuvan khomei (in the restricted sense) and the only example of altai kiomioi that we know of, one has a low fundamental of 90 Hz and harmonics not exceeding 1 KHz (14), the other four have fundamentals between 113 Hz and 185 Hz (15) (fig. 18, and the imitation fig. 19) and are close to the high fundamental borbannadir (cf. figs. 15 and 22) sung according to the two-cavity technique.

14 Folkways/Smithsonian, No. 7.

15 Folkways/Smithsonian, nº 5, 6, 8. The Song of the World, side A, track 4.

The ezengileer style – of which only one recording is known (fig. 21) – also seems close to the high fundamental borbannadir (fig. 15 and 22).

All the recordings of tuvan borbannadir, khomei and ezengileer that we have been able to examine have in common a rhythmic pulsation that we will examine later under the heading of ornamentation processes. It therefore seems that for the borbannadir, current usage allows two variants: a relatively low fundamental (75 to 95 Hz) and a melody of harmonics below 1KHz, therefore sung according to the one-cavity technique, and a fundamental higher (120 to 190 Hz) with a melody of harmonics above 1 KHz, sung using the two-cavity technique, the common feature being the rhythmic pulse.

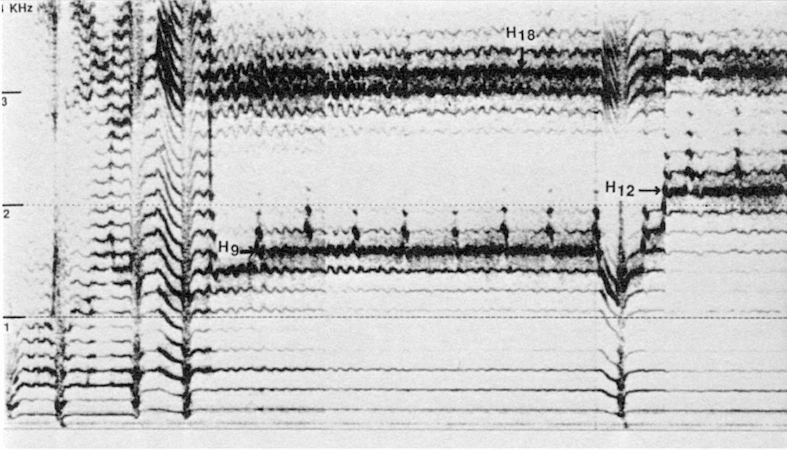

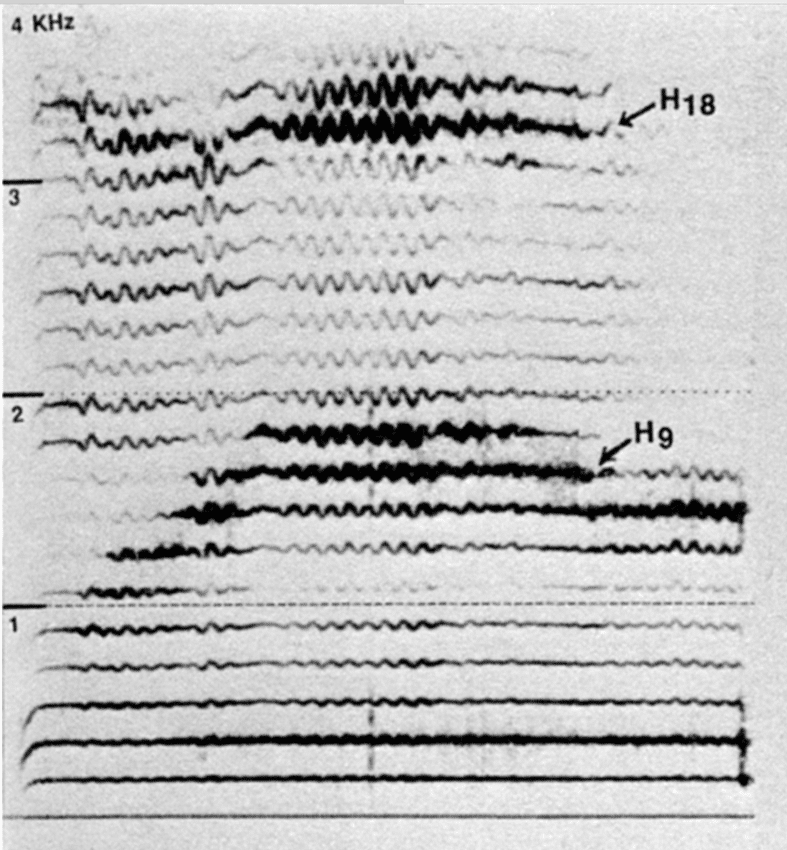

The tuvan style that is most clearly opposed to kargiraa and borbannadir (with a low fundamental) is the sigit. According to Aksenov, it is characterized by a tighter and higher fundamental, the pitch being in the middle of the small octave. The fundamental can change within a piece and can constitute the melodic voice without melody of harmonics at the beginning of verses. Unlike other tuvan styles, the upper voice does not constitute a well-characterized melody, but remains for a long time on a single pitch with rhythmic ornaments (Aksenov 1973: 15-16). See our analysis of ornamentation processes below.

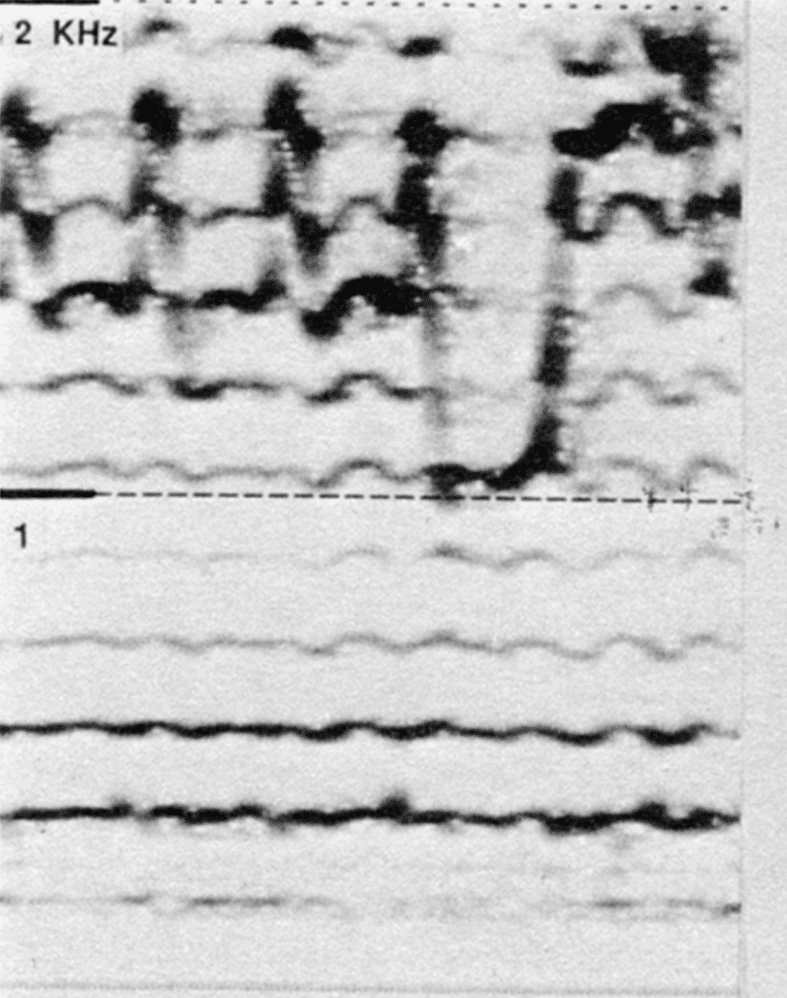

In the eleven recordings of tuva n sigit and the only example of altai sibiski that we know of, the fundamental is between 160 and 210 Hz (16). We have chosen to reproduce three sonograms (fig. 23, 24 and a brief extract fig. 18). For imitation (fig. 26), Trân Quang Hai uses the two-chamber technique.

16 Folkways/Smithsonian, nos. 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, 17. Melodia, side A, tracks 1, 2, 6, 7, 8. Le Chant du Monde, side A, track 3.

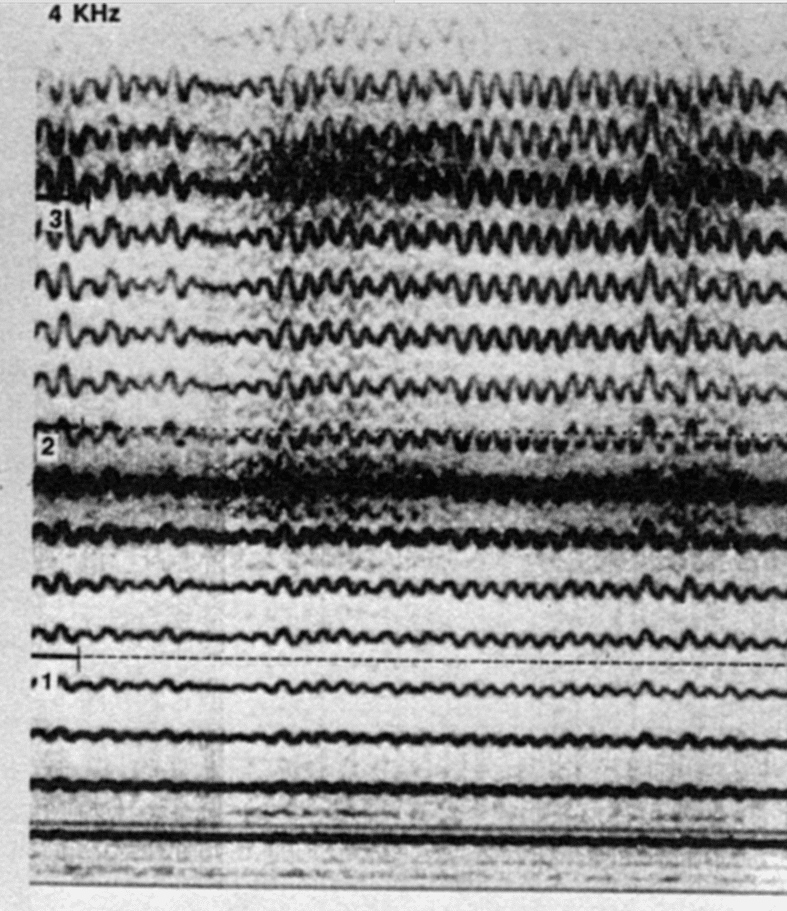

Many Mongolian songs known from recordings have a sound close to that of the sigit. The production of the harmonics is similar, but the musical style is different in that the harmonics make a real melody. This is the case with the songs of D. Sundui (fig. 25), the specialist in Mongolian overtone singing probably appearing most often on records (17). The line notes of these various discs only indicate the general term (khöömii), but we also know that he mainly sings the kevliin khöömii (“belly khöömii”); the latter style and tseedznii khöomii (“breast khöömii”) being for him “in general the same thing” (Emmert and Minegushi 1980: 48).

17 Tangent TGS 126, side B, track 1 Tangent TGS 127, side B, track 3. Victor, side A, tracks 5, 6 and 7.

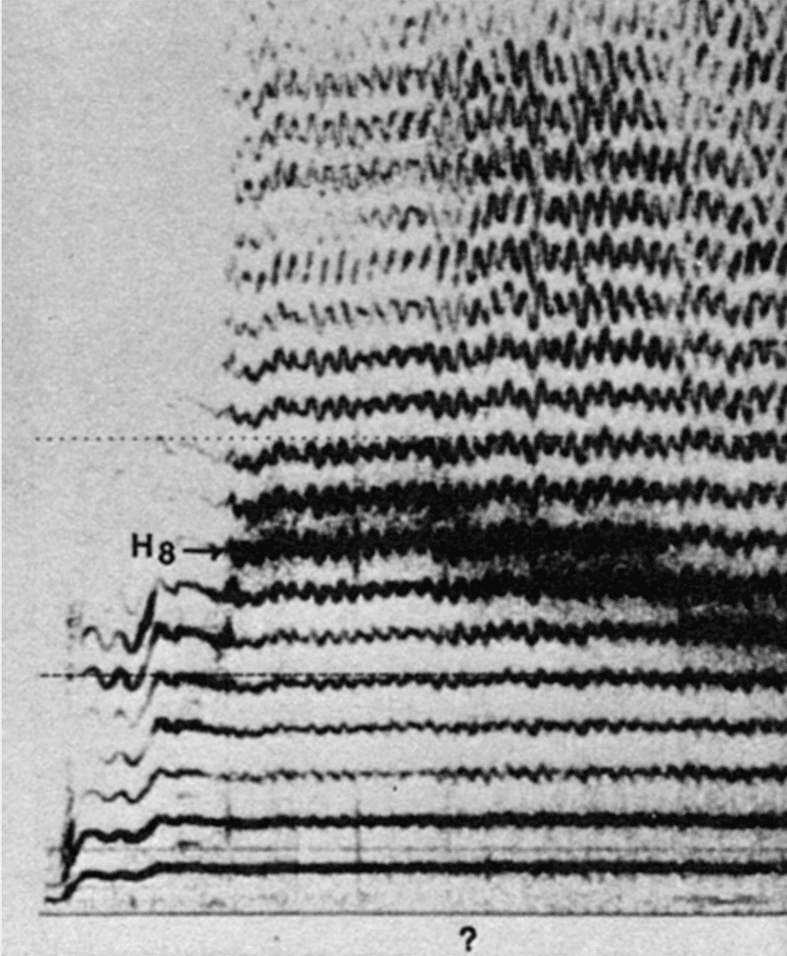

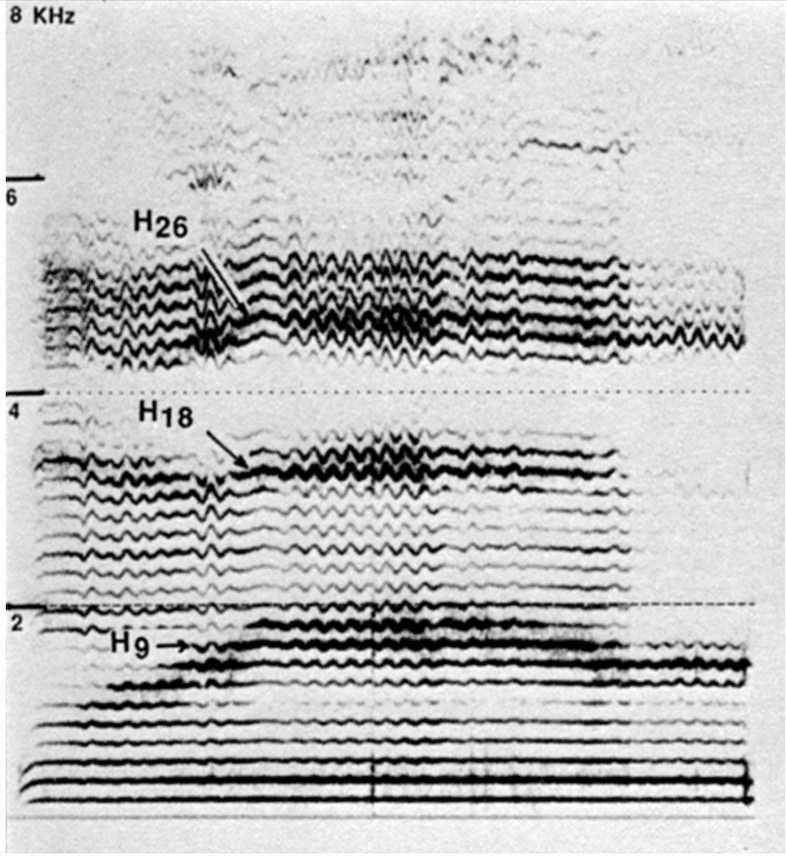

In the interview for the film Le chant des harmoniques, T. Ganbold names his favorite style, a short example of which is reproduced in fig. 29, kholgoï khöömii (“throat khöömii”) (18); while for the recording of a disc made three days earlier, he named this same style tseedznii khöömii (“chest khöömii”) (19). Did he make a mistake when recording the disc or when shooting the movie? Be that as it may, being wrong confirms what we have already suggested above, namely that the attribution of a name to a style or a technique does not seem to be a major concern for certain singers (20). However, since T. Ganbold was a student of D. Sundui who practices “belly khöömii” (or breast), we are inclined to think that “breast khöömii” is the correct term. Examination of the differences relating to muscle contractions confirms this hypothesis (see below). The other published recordings of Mongolian overtone singing, the sonograms of which we do not reproduce here because the style is not named on the records of the discs, appear to belong to this same style that D. Sundui calls (remember) “khöömii belly”, and which seems to be the most widespread in Mongolia (21).

18 According to Alain Desjacques, who provided the translation, the term kholgoï is synonymous with bagalzuuliin.

19 Cf. the notice of the CD Maison des cultures du monde, nº 4 and 6.

20 Another Mongolian singer indicated the name of khooloin khöömii (“throat khöömii”) for one piece, and tseesni khendi (translated as “ventral technique”) for another, whereas simple listening shows, and spectrographic analysis confirms that it is the same style (CD GREM, nº 32 and 33), in this case the style that D. Sundui calls kevliin khöömii (“belly khöömii”).

21 Vogue, side B, track 3. Hungaroton, side A, track 5, and side B, track 7. ORSTOM-SELAF, side B, track 2. Maison des Cultures du Monde, nº 4, 5, 6.

Very close to the sonogram of D. Sundui’s singing is the image of the recording that John Levy made in 1967 in Rajasthan (fig. 27). No documentation concerning the exact place, the name of the singer and the circumstances of the recording accompanying the magnetic tape deposited in the sound archives of the Musée de l’Homme, we are left to guesswork. It is disturbing that no recording of another singer from Rajasthan is known and no publication mentions overtone singing in this region. During his visit to the Museum of Man in 1979, Komal Kothari, director of the Rajasthan Institute of Folklore, told Trân Quang Hai that he had heard of this vocal phenomenon without having been able to listen to it himself.

The only example of a “nose khöömii” that we have is a very short six-second fragment recorded during the interview with T. Ganbold. The only difference with the “chest khöömii” (?) (cf. figs. 29 and 31) is that the singer completely closes his mouth; the melody of harmonics is then less pronounced, “drowned” in a way in the harmonics present throughout the spectrum (fig. 30 and 32).

A last style remains to be examined: the “throat khöömii” (we correct the name, cf. supra) sung by T. Ganbold (fig. 33, and its imitation by Trân Quang Hai, fig. 34). It is clearly one of the styles using the two-cavity technique. We will discuss this under the heading of muscle contractions.

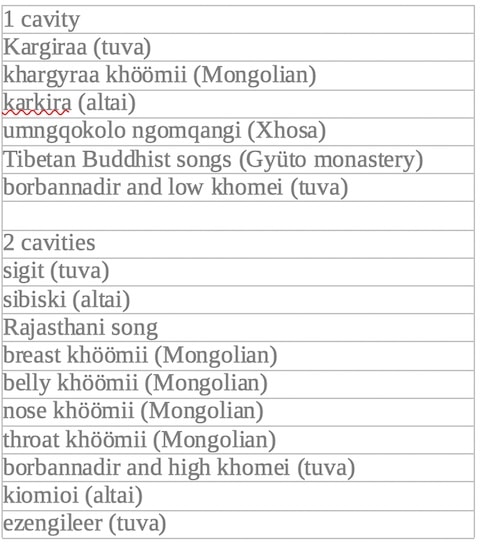

Table 1: Classification of styles according to resonators.

Muscle Contractions.

During the European tours of Mongolian and Tuvan overtone singers, Trân Quang Hai often attended concerts backstage or joined the artists in the changing rooms. He was able to see that they came back breathless and tired, their faces marked by the rush of blood. It is certainly not without reason that the pieces are very short, and that the same singer does not generally interpret more than two or three overtone songs during the same program.

While trying to reproduce the sonority of the songs as well as the tracing of the sonograms of the different styles of overtone singing, Trân Quang Hai noticed that he had to employ different degrees of contraction of the abdominal and sterno-cleido-mastoid muscles (neck muscles), and more particularly at the level of the pharynx.

In the tuvan and Mongolian kargiraa style, the abdominal muscles and the pharynx are relaxed (fig. 6 and 12). At first sight, this is not surprising, since kargiraa is the style in which the fundamental is the lowest (between 57 and 95 Hz), and to produce a low sound it seems more natural to relax the muscles than to contract them. However, to imitate the Xhosa song of South Africa as well as possible, which also uses a low fundamental (100 and 110 Hz), Trân Quang Hai had to contract the abdominal muscles and the pharynx very strongly (fig. 8). For Mongolian and Tuvan songs characterized by higher pitches (between 160 and 220 Hz), experience shows varying degrees of muscle tension. Thus, the strongest contraction appears in the tuvan sigit style (fig. 26), with a narrow air duct. Very similar are the Rajasthani song (fig. 28), the Mongolian “ches khöömii ” (?) style of T. Ganbold (fig. 29) and the “belly khöömii” of D. Sundui (fig. 25) . The latter, during an Asian music festival in Finland (22), took Trân Quang Hai’s hand to place it successively on his belly and on his throat, in order to make him feel the differences in contraction. For khargiraa khöömii, the abdominal muscles were relaxed; for “belly khöömii” (D. Sundui’s specialty), the belly was rock hard. Is this the reason for this naming? If, as D. Sundui says, “belly khöömii” and “breast khöömii” are in general the same thing (op. cit.), how to explain the two expressions? When Trân Quang Hai imitates this style, he feels a vibration at the top of the chest, at the level of the sternum. The name “belly khöömii” would then refer to the very great tension of the abdominal muscles; the denomination “Chest khöömii” would rather indicate the vibration that the singer feels at the level of the sternum. The other style used by T. Ganbold, whose name should then be corrected to “throat khöömii” (and not “chest” as he says in the film), is characterized by a melody of harmonics much less marked, “drowned” in some way in the harmonics covering the entire spectrum (fig. 33). By trying to imitate it (fig. 34), Trân Quang Hai contracts the abdominal muscles and the pharynx less, and when we place the fingers on the throat above the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple), we actually perceive a stronger vibration at this level.

22 Trân Quang Hai was artistic director for the Asian music section at the chamber music festival in Kuhmo in 1984, and as such had invited the singer D. Sundui to perform in Finland.

In the high-pitched borbannadir (fig. 20) and khomei (fig. 19), the muscle contractions seem weaker than in the sigit, but stronger than in the kargiraa.

Is muscle contraction a determinant of an individual’s style or manner of singing (23)? Trân Quang Hai manages to imitate the stylistic characteristics of tuvan sigit or Mongolian “belly khöömii” without excessive abdominal and pharyngeal contraction, but the power of the harmonic melody is markedly less and the sonority duller (fig. 37). To produce greater power and a sound resembling the recordings of Tuvan and Mongolian singers, he contracts the abdominal and sterno-cleido-mastoid muscles of the neck to the extreme.

By blocking the pharynx to obtain a very constricted air passage, it obtains a melody of harmonics more “detached” from the other harmonics of the spectrum (fig. 35). By contracting the pharynx a little less and leaving a wider air duct, it seems to have more resonance in the oral cavities; the result is a wider harmonic melody and a darker outline of all the harmonics (fig. 36). For comparison, we have reproduced a sonogram showing closed-mouth overtone emission (fig. 38).

23 We owe this question to Gilles Léothaud who asked it at the seminar of our research team when we presented our work.

The first to have suggested a relationship between the tension of certain body parts and the brilliance of harmonic sounds in overtone singing is S. Gunji. Based on a text by the German acoustician F. Winckel, he recalls that the interior walls of body cavities are soft and can be modified by tension; if the tension is high, the high frequencies will not be absorbed and the sound will be very bright, and the opposite occurs if the degree of tension is low (Gunji 1980: 136). More research in this area would be needed – including with opera singers who achieve power and bright sounds seemingly without excessive muscle tension – before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

Table 2: Classification of styles according to muscle contraction.

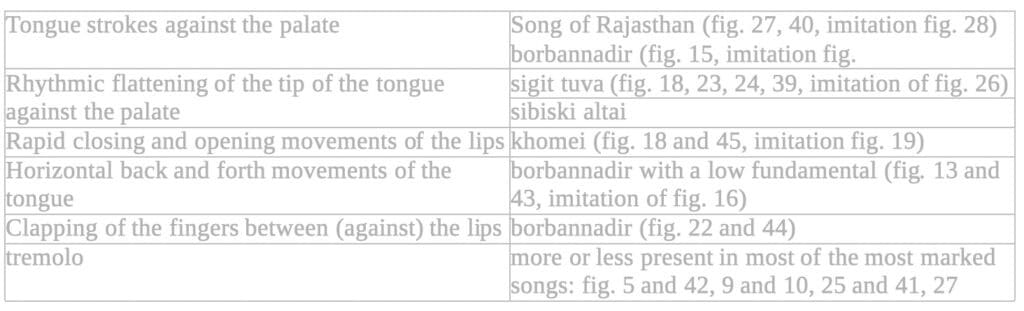

Ornamentation processes.

The sound recordings available to us present several ornamentation processes that enrich the rhythmic and harmonic texture of overtone singing. The reduction in the format of the sonograms – necessary for this publication – makes reading the ornaments difficult. We have chosen to reproduce on a larger scale eight extracts of songs already analyzed: this time the analysis of the frequency is limited to 2 KHz (and not 4 KHz), and the temporal axis is twice as large (fig. 39 to 42).

1) In the tuvan sigit and altai sibiski style, it is not an ornamentation added to the melody, but the main element of the musical style. As Aksenov says, unlike other tuvan styles, the upper voice of sigit does not constitute a well-characterized melody but rather a punctuated rhythm mainly on two pitches, the 9th and 10th harmonics of the two fundamentals (24) (Aksenov 1973: 15- 16). These punctuations follow one another at a regular rate once per second or a little closer (fig. 23, 24 and 39).

24 “an ornamented trilling and punctuating rhythm principally on two pitches (the ninth and tenth partials of the two fundamentals)”

Logically, to obtain punctuation on the harmonic immediately above the main melodic line, the volume of the anterior oral cavity must be reduced by advancing the tip of the tongue. Moving forward very quickly and moving back once per second the tip of the tongue, which is directed vertically against the palate, is quite uncomfortable. Hai found another possibility by slightly flattening the tip of the tongue against the palate, the anterior oral cavity is also shortened, and by quickly returning to the initial position, the movement of the tongue is more comfortable (fig. 26). We do not know how the singers of sigit proceed, if it is the first or the second solution that they adopt, but according to the law of least effort, we can suppose that they use the second process. On the sonogram, this punctuation is very marked on the immediately higher harmonic of the melodic line, and more weakly on the second and third harmonics above, but not on the lower harmonics, in particular those of the drone.

2) Another method of rhythmic pulsation is undoubtedly performed by strokes directed vertically against the palate. We know of two examples, one from Mongolia (25), the other from Rajasthan (fig. 27 and 40). This time, the accentuation is visible over the whole range of the sound spectrum, and in particular on H2 and 3 by vertical lines. The tongue is not advanced horizontally or flattened against the palate as in sigit, but it moves back and forth vertically (imitation fig. 28).

25 GREM, No. 2.

The line on the right side of fig. 15, representing borbannadir, shows on H13 a rhythmic punctuation close to that of sigit, and an accentuation on the lower harmonics, in particular on H3, which suggests that it is made by strokes (fig. 20) as in the case of Rajasthani singing.

3) According to Aksenov, in the ezengileer style, characterized by irregular accents (agogic), one hears in the melody of the harmonics and in the fundamental the uninterrupted dynamic pulsations of the rhythm of the gallop, the denomination of this style coming from the term “stirrup”. (1973: 16). Aksenov mentions elsewhere that the singing of borbannadir can be uninterrupted or broken; in the latter case, the intonation of v is interrupted by the closing of the lips followed by their opening, or else on x, the plosive consonant b or the nasal consonant m (26). Alekseev, Kirgiz and Levin (1990) write that this pulsating, asymmetrical rhythm of the ezengileer is produced by rapid lip vibrations, and that the term borbannadir – “used metaphorically to mean ‘rolling’” – is characterized by the same pulsating rhythm (27).

26 In the broken singing of this style the intoning of v is interrupted by the full closing of the lips followed by opening either on x the plosive voiced consonant b or on the nasal consonant m. (Aksenov 1973: 14)

27 The three authors write that the melody of harmonics is produced by rapid vibrations of the lips (In ezengileer, soft, shimmering harmonic melodies produced by rapid vibrations of the lips, are sung over a low fundamental drone). The reader will correct this bad formulation himself, because of course it is not the melody of harmonics which is produced by the vibration of the lips, but the pulsed rhythm. Similarly, the wording that the style “borbannadir is used metaphorically to mean ‘rolling'” (borbannadir, used metaphorically to mean ‘rolling’) is not very happy.

This pulsation is visible on the sonograms of khomei and ezengileer by a reading on one or two pitches of harmonics, alternately above and below the horizontal line. In the khomei example (fig. 18 and 45), there are five beats per second; in the ezengileer example (fig. 21 and 46), the beats are closer together: nine per second. To obtain a similar line, Trân Quang Hai makes rapid movements from the lower lip to the upper lip (fig. 19). On the low fundamental Borbannadir sonograms (Figs. 13 and 43), the eight beats/second pulse is reproduced in a “zigzag” pattern; to imitate it, Trân Quang Hai makes rapid movements of the tongue back and forth (fig. 16).

If the ornaments and rhythmic devices described in paragraphs 1 to 3 are exclusively realized by the phonatory apparatus, another device uses an external intervention: the striking of a finger (fingers) between (against) the lips (28) (Alekseev , Kirgiz and Levin 1990), marked on the sonograms (figs. 22 and 44) by a kind of “hatching” on H2. As these authors do not give more details, Trân Quang Hai tried all possible variants of striking, with one or more fingers, in a horizontal or vertical position, against or between the lips. But none of these tests made it possible to differentiate the irregular rhythm of the striking of the finger(s) on H2, from the regular pulsation of the upper harmonics.

28 This is how we can translate the expression “with finger strokes across the lips”. We can suppose that a finger (the index?) is placed horizontally between the lips, and that a rapid vertical back-and-forth imparts the pulsation to the overtone emission.

5) It may be unorthodox to include vibrato in ornamental processes (although some musicologists do), but we find it interesting to study it here precisely to bring out the differences but also the similarities. with other techniques. Ultimately, it’s a process like any other for enriching the sound of overtone singing and structuring time.

Frequency modulation vibrato is characterized on the sonogram by a more or less strong fluctuation of the main harmonic melody as well as of the other harmonics appearing on the tracing, drawing four to five “ripples” per second. The strongest vibrato we have heard and seen on a sonogram is by the Mongolian singer D. Sundui, whose overtone singing is otherwise characterized by the use of a wideband harmonic melody: in some places , the “top of the wave” of one harmonic almost touches the “bottom of the wave” of the higher harmonic (fig. 25 and 41). On H8 for example, the vibrato oscillates between 1620 and 1790 Hz, the range of the vibrato being 170 cents, that is to say between three-quarters of a tone and a whole tone. This artist, having studied Western classical singing at the Moscow Conservatory (29) – he also sings using the technique of overtone singing, tunes by composers such as Tchaikovsky and Bizet (Batzengel 1980: 52) – one would be tempted to suppose that his very marked vibrato was acquired during his studies at the conservatory (30). The singer from Rajasthan (fig. 27), of whom nothing is known, also has a very strong vibrato, also combined with a melody of broad-band harmonics.

29 Verbal communication from D. Sundui to Trân Quang Hai during the festival in Finland, 1984.

30 In opera and concert singing, the undulation of the vibrato is described as almost sinusoidal, with an ambitus of the order of +50 Hz (Sundberg 1980: 85), i.e. quarter tone.

Vibrato can be combined with other ornamental devices, such as the licking of the tongue against the palate in the song of Rajasthan (fig. 27), or the rhythmic flattening of the tongue against the palate in the sigit (fig. 26). In this last example, we can count four vibrato oscillations for a rhythmic accent per second. The sonogram of fig. 18 is particularly interesting since it allows us to compare the layout of the vibrato (on the right for the sigit) with the rhythmic pulsation (on the left for the khomei), the two processes being used successively by the same singer in the same piece.

Vibrato can be combined with other ornamental devices, such as the licking of the tongue against the palate in the song of Rajasthan (fig. 27), or the rhythmic flattening of the tongue against the palate in the sigit (fig. 26). In this last example, we can count four vibrato oscillations for a rhythmic accent per second. The sonogram of fig. 18 is particularly interesting since it allows us to compare the layout of the vibrato (on the right for sigit) with the rhythmic pulsation (on the left for the khomei), the two processes being used successively by the same singer in the same piece.

Table 3 Ornamentation

To what extent does spectrographic analysis show individual differences in vocal output between singers using the same style? This question deserves an in-depth analysis, but with many more recordings of the same style sung several times by the same singer, and by different singers. The examination of the sonograms that we have carried out nevertheless allows us to give a first answer: it appears that there are indeed individual differences (which we can assume to be of the same order as the differences in style and voice of the singers opera, for example). We have seen that for the four styles sung by T. Ganbold, the sound spectrum is characterized by a significant zone of harmonics above 4 KHz, which is not the case with the other singers whose sonograms we publish . Two sonograms of the sigit style sung by two different singers show in one a kind of “harmonic drone” above the melody of harmonics (fig. 23), absent in the other (fig. 24). Similarly, the “harmonic drone” is very strong in one kargiraa singer (fig. 5), and absent in another (fig. 9 and 10). Of course, one must be careful not to draw definitive conclusions with so few examples, because especially in the acute zones, certain differences can also result from the recording conditions (equipment, environment).

But differences are also noticeable in lower areas: in many sonograms, harmonic 1 is very weak (fig. 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 18, 22), while in others , it is on the contrary very marked (fig. 15, 21, 25, 27, 29, 30, 33). Is the intensity of H1 a function of style? We don’t think so: in any case, the sigit style can obviously have a weak (fig. 18) or strong (fig. 23 and 24) H1. The intensity of harmonic 1 seems to be rather an individual characteristic of singers. With T. Ganbold, H1 is very marked whatever the style (remember that he is the only singer for whom we have recordings of four styles: fig. 11, 29, 30, 33). Similarly, all the sonagrams of Trân Quang Hai songs have a very marked harmonic 1. However, we have at least one sonogram showing for the same singer a weak H1 for one style and a strong H1 for another (fig. 14). Again, research should be continued.

Should we speak of “triphonic singing” when singers bring out a second drone either in the treble with harmonic 18 (fig. 23) or harmonic 44 (fig. 5), or in the bass with the harmonic 3 (fig. 15)? In the first case, the high-pitched hiss of this “harmonic drone” can hardly be called a third voice. In the second case, the author of the note in any case thinks that in the borbannadir in question, this fifth which one hears very clearly above the octave of the fundamental “gives rise as a result a song in three voices” (31). However, in both cases there is no third voice independent of the fundamental and the melody of harmonics. These are clearly individual variants which, as regards the drone in the fifth (H3), Trân Quang Hai imitates well (fig. 20). These songs are of the same nature as all the others analyzed in this article, and we do not think there is any need to change terminology.

31 Translation of B. Tchourov’s notice by Philippe Mennecier (personal communication). The same singer performed two sigit-style pieces and two khomei-style pieces that do not include this “drone in the fifth” (Melodia, side A, tracks 1 to 4).

We have saved for the end two sonagrams representing exercises in style (and not traditional styles!), in which Trân Quang Hai demonstrates all his virtuosity.

In fig. 47, he inverts the usual design of a low drone and a melody of harmonics in the high, to make from changing fundamentals a fixed pitch in the high. Thus, the 1380 Hz “harmonic drone” is realized successively by H12, 9, 8, 6, 8, 9, 12, as the fundamentals change up A1, Re2, E2, A2 and back down to A1.

In fig. 48, the exercise is even more difficult, since it simultaneously presents an ascending scale for the fundamentals and a descending scale for the harmonics, and vice versa.

Reproduced here for the scientific interest (and the pleasure) that comes from exploring the physiological limits of the human voice, these technical possibilities are not exploited in the traditions of Central Asia and South Africa. There is no doubt that they will soon be used by composers of contemporary music in the West, some of whom, since Stimmung (1968) by Stockhausen, seek to enrich vocal techniques by means of overtone singing.

Bibliography

AKSENOV A.N., 1973, “Tuvin Folk Music”. Asian Music 4(2): 7-18. (Excerpts translated from Tuvinskaia narodnaia muzyka, Moskou 1964)

ALEKSEEV Eduard, Zoya KIRGIZ and Ted LEVIN, 1990, Tuva-Voices from the Center of Asia disc record.

BATZENGEL, 1980, “Urtiin duu, xöömij, and morin xuur”. In R. Emmert and Y. Minegushi (eds.), Musical Voices of Asia 52-53. Tokyo Heibonsha Publishers.

BOREL-MAISONNY Suzanne and Michèle CASTELLENGO, 1976, “X-ray study of oropharyngeal movements during speech and instrumental playing”, Bulletin du Groupe d’Acoustique Musicale 86 (University of Paris VI).

DARGIE David, 1988, Xhosa Music. Its techniques and instruments, with a collection of songs. Cape Town and Johannesburg David Philip.

DESJACQUES Alain, 1988, “A phonetic consideration of some Mongolian overtone vocal techniques”. Bulletin of the Center for Oriental Music Studies 31: 46-45 (Paris).

EMMERT Richard and Yuki MINEGUSHI (ed.), 1980, Musical Voices of Asia. Tokyo Heibonsha Publishers.

GUNJI Sumi, 1980, “An Acoustical Consideration of Xöömij”. In R. Emmert and Y. Minegushi (ed.), Musical Voices of Asia 135-141. Tokyo Heibonsha Publishers.

HAMMAYON Roberte, 1973, Notice of the disc Chants mongols et bouriates. Museum of Man collection. Vogue LDM 30138.

HARVILAHTI Lauri, 1983, “A two voiced-song with no words”. Suomalais-ugrilaisen seuran aikakauskirja 78: 43-56 (Helsinki).

HARVILAHTI Lauri and KASKINEN H., 1983, “On the Application Possibilities of Overtone Singing”. Suomen Antropologi i Finland 4: 249-255 (Helsinki).

LEIPP Émile, 1971, “The acoustic problem of overtone singing”. Bulletin of the Musical Acoustics Group 58: 1-10. University of Paris VI.

LEOTHAUD Gilles, 1989, “Acoustic and musical considerations on overtone singing”, Voice Institute, Dossier nº 1: 17-44. Limoges.

PAILLER Jean-Pierre, 1989, “Video examinations of Mr. Trân Quang Hai”. Voice Institute, File #1: 11-14. Limoges.

PETROV Valérii and Boris TIKHOMIROV, 1985, Note for the disc Voyage en URRS vol. 10 Siberia, Far East, Far North.

SAUVAGE Jean-Pierre, 1989, “Clinical observation of Mr. Trân Quang Hai”. Voice Institute, File #1: 3-10. Limoges.

SUNDBERG Johan, 1980, “Acoustics, IV The voice”. In Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 1: 82-87. London Macmillan.

TRÂN Quang Hai, 1989, “Achieving Overtone Singing”. Voice Institute, File #1: 15-16. Limoges.

TRÂN Quang Hai and Denis GUILLOU, 1980, “Original Research and Acoustical Analysis in connection with the Xöömi Style of Biphonic Singing”. In R. Emmert and Y. Minegushi (eds.), Musical Voices of Asia: 162-173. Tokyo Heibonsha Publishers.

WALCOTT Ronald, 1974, “The Chöömij of Mongolia A Spectral Analysis of Overtone Singing”. Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology 2(1): 55-60.

ZEMP Hugo, 1989, “Filming Voice Technique: The Making of ‘The Song of Harmonics'”. The World of Music 31(3): 56-85.

Discography (For convenience, references in text and captions are to publishers rather than to disc titles, many of which look alike.).

GREM, G 7511. Mongolia. Music and songs of popular tradition. 1 CD. Recordings and notice by X. Bellenger. 1986.

Hungaryroton, LPX 18013-14. Mongol Nepzene (Mongolian folk music). 2 discs 30 cm. Recordings and record of Lajos Vargyas. Unesco Cooperation, ca. 1972. (Mongolian Folk Music reissue, 2 CDs, HCD 18013-14, 1990).

The Song of the World, LDX 74010. Voyage en URRS vol. 10: Siberia, Far East, Far North. 1 disc 30 cm. Note by V. Petrov and B. Tikhomirov. 1985.

House of World Cultures, W 260009. Mongolia. Vocal and instrumental music. 1 compact disc, “Unpublished” series. Note by P. Bois. 1989.

Melodia, GOCT 5289-68. Pesni i instrumental’nye melodii tuvy (Songs and instrumental melodies of Tuva). 1 disc 30 cm. Note by B. Tchourov.

ORSTOM-SELAF, Ceto 811. Mongolia. Music and songs from Altai. 1 disc 30 cm. Recordings and notes by Alain Desjacques. 1986.

Smithsonian/Folkways SF 40017. Tuva-Voices from the Center of Asia. 1 CD. Recordings and notes by E. Alekseev, Z. Kirgiz and T. Levin. 1990.

Tangent TGS 126 and 127. Vocal Music from Mongolia; Instrumental Music from Mongolia. 2 discs 30 cm. Recordings and records by Jean Jenkins. 1974.

Victor Records, SJL 209-11. Musical Voices of Asia (Asian Traditional Performing Arts 1978). 3 discs 30 cm. Recordings by S. Fujimoto and T. Terao, notes by F. Koizumi, Y. Tokumaru and O. Yamaguchi. 1979.

Vogue LDM 30138. Mongolian and Buryat songs. 1 disc 30 cm. Recordings and notes by Roberte Hamayon. Museum of Man collection. 1973.

Filmography.

The Song of Harmonics (English version The Song of Harmonics). 16mm, 38 mins. Authors: Tran Quang Hai and Hugo Zemp. Director: Hugo Zemp. Coproduction CNRS Audiovisuel and French Society of Ethnomusicology, 1989. Distribution CNRS Audiovisuel, 1, place Aristide Briand, F-92195 Meudon.

Annex – Sonograms Readings

In the film Le chant des harmoniques, the sonograms in real time are reproduced according to a scale of colors which seemed to us the most readable. For the black and white print of this review, we have chosen to photograph the inscription on continuous paper that the Sona-Graph provides, where the degrees of blackness correspond to the degrees of intensity of the harmonics.

Since harmonic melodies never exceed the upper limit of 3000 Hz, the spectrographic analysis in this article was limited to 4 KHz. However, to be sure that possible formant areas in higher frequencies do not escape the analysis, we examined all the chosen examples with a grid up to 8 KHz. Only the Mongolian singer T. Ganbold exceeds 4 KHz, not with the melody of harmonics, but with a third zone of formants (probably affecting the timbre, but not the outline of the melody of harmonics). We reproduce the sonograms of two recordings analyzed first at 4 KHz (fig. 29 and 30), then at 8 KHz (fig. 31 and 32).

Previous models of the Sona-Graph could only print an inscription corresponding to 2.4 seconds, respectively 4.8 seconds if the magnetic tape was read at half speed. The Sona-Graph 5500 DSP can analyze and write on continuous paper for up to 3 minutes. To reproduce the sonograms on a magazine page, we had to choose the maximum duration of the recording, the spread of the signal as a function of time, while taking care that the different harmonics were readable. Printing, for reasons of economy, two sonograms on one page, complete with substantial captions, we felt that a maximum duration of 14 seconds was the best compromise. Of course, a larger reproduction would give increased readability, but given that the number of pages of the article and the cost of photoengraving were not to be increased, the reduction chosen seemed acceptable to us. To facilitate comparison, the majority of the sonograms (fig. 3 to 38, 47 and 48) have been reproduced at the same scale. If the inscription covers the entire width of the “satzspiegel”, then it is a 14-second signal; if two sonograms of substantially equal length share the same surface, the signal is obviously half as short, i.e. approximately 7 seconds. On the other hand, the inscription of the first two sonograms had to be compressed in order to be able to reproduce the entire scale of the fundamentals (20 seconds for fig. 1, 28 seconds for fig. 2).

For reasons of readability, we have reproduced, on a larger scale, eight extracts of songs already analyzed (fig. 39 to 46): this time the analysis of the frequency is limited to 2 KHz (and not to 4 KHz), and the time axis is twice as large, which represents for each sonogram a duration of approximately 3 seconds.

Fig. 1: Harmonic scales with different pitches of the fundamental (90 to 180 Hz on a diatonic scale), by Trân Quang Hai. One cavity technique

Strongly nasalized voice. Pronunciation marked with vowels. H1, 2 and 3 of the drone very marked. With the lowest fundamental (90 Hz), harmonics 4 (360 Hz) to 12 (1080 Hz) can be used to create a melody. With the highest fundamental (180 Hz), only harmonics 3 to 6 (1080 Hz) stand out. Second harmonic zone between 2500 and 4000 Hz, separated from usable harmonics by a “white zone” on the sonogram.

Fig. 2: Scales of harmonics with different pitches of the fundamental (110 to 220 Hz, according to a diatonic scale), by Trân Quang Hai. Two-cavity technique.

Nasalized voice. H1 and 2 of the drone very marked. The well traced harmonics on the sonogram reach the upper limit of 2200 Hz with H10 in the case of the highest fundamental at 220 Hz, and H20 in the case of the lowest fundamental, an octave lower (110 Hz). The exploitable harmonics for a melody are in the first case H4 (880 Hz) to H10 (2200 Hz), and in the second case H6 (660 Hz) to H20 (2200 Hz).

Fig. 3: Harmonic scales with stable drone, by Minh-Tâm, daughter (17) of Trân Quang Hai. One cavity technique.

H1 (240 Hz), 2 and 3 of the drone very marked. Harmonics usable for a melody H3, 4 and 5 (1200 Hz). For a female voice, because of the height of the higher fundamental (here 240 Hz), the number of usable harmonics for a melody is very limited.

Fig. 4: Harmonic scales with stable drone, by Minh-Tâm, daughter (17) of Trân Quang Hai. Two-cavity technique.

Nasalized voice. H1 (270Hz). Usable harmonics for a melody H4 (1080 Hz), 5, 6, 7, 8 (2160 Hz). H8 causes H12 and 13 to appear in the treble zone.

Fig. 5: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 18. Kargiraa style, “Artii-sayir” piece by Vasili Chazir.

Pronunciation marked with vowels. H1 (62 Hz), 2 and 3 drone very weak. Melody of harmonics H6 (375 Hz), 8, 9, 10, 12 (750 Hz). Second octave harmonic melody zone, between H12 (750 Hz) and H24 (1500 Hz). Acute “harmonic drone” H44 (2690 Hz), more pronounced when the vowel a is pronounced (with a sort of “gray column” between 1500 and 2700 Hz. (Musical transcription of this piece in the CD instructions).

Fig. 6: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the kargiraa tuva style of fig. 5.

One-cavity technique, pronunciation marked with vowels. Mouth open, except when the melody of harmonics goes down to H6 (then mouth closed with pronunciation of the consonant m). Pharyngeal and abdominal relaxation. H1 (70 Hz), 2, 3 and 4 of the drone very marked, H2 and 4 a little more than H1 and 3. Melody of wideband harmonics H6 (420 Hz), 8, 9, 10, 12 (840 Hz ). Second octave harmonic melody zone, between H18 (1260 Hz) and H24 (1680 Hz). Very weak third harmonic melody zone, between 2100 and 2400 Hz.

Fig. 7: Xhosa (South Africa). Save D. Dargie, Sound Library Museum of Man BM 87.4.1. Style imitating the playing of the umrhubhe musical bow, by Nowayile.

Alternation of two fundamentals at the interval of a tone. H1 (100Hz and 110Hz), very low; Bumblebee H2, 3 and 4 marked. Harmonic melody H4 (400Hz), 5, 6 (600Hz) when fundamental is 100Hz; and H4 (440 Hz) and H5 (550 Hz) when the fundamental is at 110 Hz. Second melody zone of harmonics between 800 and 1200 Hz. Third zone weaker at 2400 Hz; for example, when the harmonic melody is on H6, harmonics 10 and 12, as well as H24 are very strong. (Musical notation in Dargie 1988: 59)

Fig. 8: Trân Quang Hai’s imitation of the Xhosa song in fig. 7.

One cavity technique. Voice slightly nasalized, mouth less open than in the kargiraa style. Pharyngeal and abdominal contraction. H1 (100 and 110 Hz), 2, 3 and 4 marked. Melody of harmonics H4 (400Hz), 5, 6, 8 (800 Hz). Poorly mastered technique. Absence of second and third zone in the treble.

Fig. 9: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 1. Kargiraa “Steppe” Style, by Fedor Tau. Beginning of the song.

Pronunciation marked with vowels. H1 (67Hz) very low; H1 is lowered by a minor third (57 Hz) when the vowel i is pronounced. At the same time, the harmonic melody also drops by a minor third, the harmonic remaining the same (H8). Broadband harmonic melody H8 (536 Hz) and 456 Hz), 9, 10, 12 (804 Hz). Second melody zone of harmonics between H16 (1072 Hz) and H30 (2010 Hz). For the back vowels o, ɔ, a, the second harmonic melody zone is at octave H8 — H16, H9 — H18, H10 — H20, H12 — H24.

Fig. 10: Resumption of the song of fig. 9. Same melody of harmonics, but difference of second zone due to difference of vowels. For the front vowels i, e, , the second melody zone of harmonics is higher the vowel e at the start of the repeat (fig. 10) H8 — H32 (= double octave); the vowel i H9 — wide band from H28 to 30.

Fig. 11: Mongolia. Film The song of the harmonics. Khargiraa khöömii style, demonstration for the interview, by T. Ganbold.

H1 (85Hz) very low; H2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 of the drone very marked. Weak harmonic melody, with odd harmonics H13 (1105 Hz), 15, 17, 19, 21 (1785 Hz). In the treble, a zone of weak harmonics between H28 and H 30 (2630 to 2800 Hz).

Fig. 12: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the Mongolian khargiraa khöömii style of fig. 11

Two-cavity technique. H1 (90 Hz) as well as H2, 3, 4 and 5 very marked. Harmonic melody with even harmonics H12 (1080 Hz), 14, 16, 18, 20 (1800 Hz). Pharyngeal and abdominal relaxation.

Fig. 13: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 14. Piece titled borbannadir, by Anatolii Kuular.

Obviously the kargiraa and borbannadir styles follow one another. Characteristic line of kargiraa, with six beats/second vibrato in the form of undulations. H1 (95Hz) low. In the borbannadir part, H1 (95 Hz) weak; H2, 3 and 4 marked. Eight beats/second “zigzag” pulse over the melody of broadband harmonics H7 (685 Hz), 8, 9 and 11 (1045 Hz).

Fig. 14: Same part as fig. 13, a little further.

Obviously three styles. In the first segment, kargiraa and borbannadir styles linked together, with low H1 (95 Hz). After a short interruption, second segment in a different style, with an octave jump of the fundamental, H1 (190 Hz) and H2 well marked. Broadband harmonic melody, with seven beats/second “zigzag” pulse, H9 (1710 Hz), 10 and 12 (2280 Hz

Fig. 15: Tuva (USSR). Melodia disc, side A, track 5.

Borbannadir style, piece “Boratmoj, Spoju Borban”, by Oorzak Xunastar-ool. H1 (120 Hz) and 2 marked. H3 of the very marked drone (we can hear this second drone in the fifth). Melody of harmonics H8 (980 Hz), 9, 10 and 12 (1440 Hz). Rhythmic accents visible especially on H3, 12 and 13.

Fig. 16: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the borbannadir style of fig. 13.

One cavity technique. Nasalized emission, mouth almost closed, pronunciation of the vowel o. H1 (95Hz), 2 to 5 very marked. Rapid forward and backward tongue movements “zigzag” pulsing over the melody of broadband harmonics H9 (855 Hz) to 13 (1235 Hz)

Fig. 17: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the unidentified style of fig. 14.

2-cavity technique. Strong nasalization, pharyngeal and abdominal contraction. H1 (190Hz) and 2 very marked. Rapid flattening of the tip of the tongue against the palate, and simultaneous trembling of the lower jaw pulsating “zigzag” over the melody of broadband harmonics H6 (1140 Hz) and 8 (1520 Hz).

Fig. 18: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 8. Khoomei and Sigit Styles, by Tumat Kara-ool.

H1 (175Hz). For khoomei, low H1; H2 and 3 marked. Broadband harmonic melody H6 (1050 Hz), 8, 9, 10 (1750 Hz). Rhythmic pulsation visible as vertical lines directed alternately up and down from the horizontal line indicating the melody of harmonics. For the sigit (cf. also fig. 21 and 22), H1, 2 and 3 of the weak drone. Harmonic melody H12 (2050 Hz) and ornament H13; the other harmonics not appearing on the extract of this sonogram.

Fig. 19: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the khoomei tuva style of fig. 18.

Two-cavity technique. Slightly nasalized voice. Moderate pharyngeal contraction. Mouth less open than for the sigit. Rhythmic movements from lower lip to upper lip: rhythmic pulsation visible as vertical strokes alternately above and below the horizontal line.

Fig. 20: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the borbannadir tuva style of fig. 15.

wo-cavity technique. Nasalized voice. Moderate pharyngeal contraction as in fig. 18a, but the mouth even less open, rounded. Rhythmic licks against the palate, well marked on H3 of the drone and on the upper harmonics. H1 (175 Hz), 2 and 3 very marked; melody of harmonics H10 (1750 Hz) and H 12 (2050 Hz).

Fig. 21: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 15. Ezengileer style, by Marzhimal Ondar.

H1 (120 Hz), 2, 3, 4 of the drone very marked. Melody of harmonics H6 (720 Hz), 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 (1440 Hz). The layout is characterized by “zigzag” rhythmic accents on 2 or 3 harmonics (the chosen extract does not include the tapping of fingers on a bowl of tea, indicated on the CD instructions). In the treble, a second zone of harmonics between H22 and H24 (2880 H

Fig. 22: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 13. Piece entitled “Borbannadir with finger strokes”, by Tumat Kara-ool.

H1 (180Hz) low. Irregular “hatch” on H2, rhythmically different from the ripple-like vibrato marked on the upper harmonics. Melody of harmonics H6 (1080), 8, 9, 10 (1800 Hz). Second octave harmonic melody zone, except H10 — H18.

Fig. 23: Tuva (USSR). Smithsonian/Folkways CD, No. 3. Style sigit, piece “Alash” by Mergen Mongush.

Beginning sung with lyrics in natural voice. Momentary lowering of the fundamental to a minor third. H1 (190 Hz), drone 2 and 3 marked. Harmonic melody H8 (1520 Hz), 9, 10 and 12; rhythmic ornaments on H10 and 13. In the treble, “harmonic drone” in the octave of the harmonic melody (H9 — H18) and in the fifth (H12 — H18). Harmonic rejection zone between the drone (H1 to H3) and the harmonic melody, and between this and the high drone (H18).

Fig. 24: Tuva (USSR). Melodia disc, side A, track 1. Style sigit, piece “Reka Alas” (same piece as fig. 23).

Fig. 25: Mongolia. Tangent record, side B, track 1. Piece entitled “Mouth music”, by Sundui (see also the film Le chant des harmoniques). Style not named on record label, but arguably “belly khöömi”, Sundui’s favorite style.

H1 (210 Hz) and 2 marked, except when the harmonic melody is on H12. Broadband harmonic melody H5 (1050 Hz), 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 12 (2510 Hz). Vibrato in the form of undulations.

Fig. 26: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the sigit tuva style of fig. 23.

Two-cavity technique. Strong nasalization. Abdominal and pharyngeal contraction. Narrowing of the air column. To obtain the rhythmic ornaments (H10 from melodic line H9, and H13 from melodic line H12), the tip of the tongue is slightly flattened against the palate. H1 (145 Hz) and H2 very marked. Same harmonic melody as fig. 23 and 24. Absence of a second zone in the treble, as in fig. 24.

Fig. 27: Rajasthan. Recording J. Levy. Sound library of the Musée de l’Homme BM78.2.1.

H1 (170 Hz) and 2 very marked. Harmonic melody H5 (850 Hz), 6, 8, 9,10, 11, 12, 13, 16 (2720 Hz), broadband. Rhythmic accents, no doubt to imitate the playing of the jew’s harp. Largest range of all the pieces analyzed in this article.

Fig. 28: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the Rajasthani song of fig. 2

Two-cavity technique. Strongly nasalized voice. Strong pharyngeal and abdominal contraction (as for the sigit). Rhythmic licks against the palate, resulting in vertical lines as shown in fig. 27. H1 (150 Hz), H5 (750 Hz) to H 16 (2400 H z).

Fig. 29: Mongolia. Probably style tzeedznii khöömii (“chest khöömii”), mistakenly called in the film The Song of Harmonics bagalzuuriin khöömi, (“throat khöömi”). Demonstration for the interview, by T. Ganbold.

H1 (180 Hz) marked, H2 very marked. Melody of harmonics H8 (1440 Hz), 9, 10 (1800 Hz). In the treble, 2nd octave zone (H18 at 3240 Hz).

Fig. 30: Same singer. Style khamryn khöömii (“nose khöömii”). H1 (170 Hz), 2 and 3 marked. Very low H8, 9 and 10 harmonic melody, “drowned” in harmonics spanning the entire spectrum.

Fig. 31: Same signal as fig. 29.

Analysis at 8 KHz, showing a third broadband zone above 4000 Hz.

Fig. 32: Same signal as fig. 30.

Analysis at 8 KHz, showing a third broadband zone above 4000 Hz.

Fig. 33: Mongolia. Probably style bagalzuuliin khöömii, (“throat khöömii”), mistakenly called in the film The Song of Harmonics tseedznii khöömi (“chest khöömi”). Demonstration for the interview, by T. Ganbold. Mouth wide open. H1 (170 Hz), 2, 3, 5, 6 of the drone very marked. Melody of harmonics H8 (1360 Hz), 9, 10 (1700 Hz). In the treble, a second zone of broadband harmonics H16 to 20 (2720 to 3400 Hz). An analysis at 8000 Hz (not reproduced here) shows a very marked third zone above 4000 Hz.

Fig. 34: Imitation by Trân Quang Hai of the style of fig. 33.

Two-cavity technique with the back of the tongue bitten by the molars. Pharyngeal contraction with narrowing of the air column, neck musculature “lifted up”. Mouth wide open, lips slightly stretched as if to pronounce the vowel i. H1 (170 Hz), 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 of the drone very marked. Melody of harmonics H8 (1360 Hz), 9, 10 (1700 Hz).

Fig. 35: Essay? by Tran Quang Hai.

H1 (220Hz); melody of H8 harmonics. Strong abdominal and pharyngeal contraction. Very tight air duct. The vibration is felt most strongly above the Adam’s apple.

Fig. 36: Essay? by Tran Quang Hai.

H1 (220Hz); melody of H8 harmonics. Strong abdominal and pharyngeal contraction. Wider air duct. The vibration is felt most strongly below the Adam’s apple.

Fig. 37: Essay by Tran Quang Hai.

H1 (220Hz); melody of H8 harmonics. Abdominal and pharyngeal relaxation. Low intensity; to obtain a black trace, it was necessary to compensate by increasing the input level of the Sona-Graph

Fig. 38: Essay by Tran Quang Hai.

H1 (220Hz); melody of H8 harmonics.Closed mouth. Contractions as in fig. 36. Low Intensity; to obtain a black trace, it was necessary to compensate by increasing the input level of the Sona-Graph.

Fig. 39: Sigit tuva (see fig. 23). Rhythmic ornaments “in punctuation” on H10, combined with vibrato.

Fig. 40: Song of Rajasthan (cf. fig. 27). Rhythmic accents marked by vertical lines across the entire spectrum.

Fig. 41: Mongolian “belly Khöömii” (cf. fig. 25). “Ripple” Vibrato

Fig. 42: Kargiraa tuva (see Fig. 5). vib

Fig. 43: Borbannadir tuva with low fundamental (cf. fig. 13). “Zigzag” pulsing over the melody of broadband harmonics.

Fig. 44: Borbannadir tuva with acute fun damental (cf. fig. 22). Rhythmic “hatch” accents on H2 by tapping finger(s) on lips.

Fig. 45: Khomei tuva (see fig. 18). Rhythmic pulsation marked by vertical lines alternately above and below the horizontal line.

Fig. 46: Ezengileer tuva (see fig. 21).

Rhythmic accents marked by vertical lines alternately above and below the horizontal line.

Fig. 47: Experimentation of a “harmonic drone” in the treble, with variation of the fundamental, by Trân Quang Hai.

Two-cavity technique. Strongly nasalized voice. Pharyngeal and abdominal contraction. Scale rising from fundamentals A1 (135 Hz), Re2, E2, A2 (270 Hz), and descending to A1. 1380 Hz “harmonic drone” performed successively by H12, 9, 8, 6, 8, 9, 12.